Next up in our RWS Archive series is Mildred Elsi Eldridge RWS, an artist whose work, though often overlooked, demonstrates an incredible and prescient understanding of the interrelations of human power structures and the natural world.

In this piece, Edith gives us some insight into Eldridge's life and career, explaining why you would be greatly mistaken in thinking of her work as nothing but 'pretty pictures of birds and flowers'.

Mildred Elsi Eldridge RWS, 1909-1991, has been sadly overlooked as an artist. This may be due to her early rejection of the London art scene, or her sporadic output; but she has produced some works of genius, and deserves recognition. Perhaps one reason she is not better known is that her work explores a theme which has not been particularly fashionable until recently: the fraught relationship of humanity and nature. Now that we are awakening to the fact of our existence in an era of mass extinction and climate crisis, artists like Eldridge who were making work about this in the mid-20th century, provide useful insight.

Carolyn Trant, in her book Voyaging Out: British Women Artists from Suffrage to the Sixties, refers to her as an eco-feminist.[1] Eco-feminism is a theoretical framework from the mid-seventies, which acknowledges that the subjugation of women is tied to that of the natural world. To apply this to Eldridge is anachronistic, and I cannot imagine her welcoming the label. However, her work can inform an eco-feminist philosophy today. It has been easy to ignore a woman artist who painted pretty birds and flowers for greetings cards. But once you know what her larger concept pieces look like, it is impossible to view her simpler works in the same way.

She is known for nature studies on Medici cards. The RWS collection contains two beautiful sheets of studies by her: one of squirrels, one of blue tits. In my blog about Robert Hills, I discussed the difference between his studies and finished pieces. Hills’ studies showed an inspiring curiosity about animals, which can also be seen in those of Eldridge. On the squirrel sheet, for example, there are multiple drawings of their feet from different angles. You can really sense her focus and dedication to her subject. In Byron Rogers’ enjoyable biography of her husband R.S. Thomas, she is described collecting specimens, being given them by children in the parish and R.S. himself. “She hung dead owls in the apple tree, waiting for the skeletons to emerge, when they would join the severed heads already on the mantelpiece in the hall.”[2]

Mildred Elsi Eldridge, Study of a Grey Squirrel, 1968, watercolour on paper, RWS Diploma Collection, 28x39cm

Eldridge uses watercolour completely differently to Hills, despite their similarity in realistically depicted subject matter. Hills paints full wet washes, his pigment spreading fluidly across the masses of tone which make up the images. Eldridge paints with a dry brush, achieving texture by repetitive cross hatching. When I first encountered her work, I felt frustrated by this failure, as I saw it, to use the medium to its full potential. Why deny the wateriness of watercolour in favour of a style which could be done in coloured pencils?

For Hills, obsessive fascination with nature became slightly conventional, stiff compositions in his finished work. Eldridge, on the other hand, expanded into complex and mysterious compositions which explore the relationships of humans to nature. Having seen these larger oils, particularly The Dance of Life [3], I began to understand her watercolours better. She combines short sharp mark making with muted colours to evoke a world of flickering translucence and movement. Looking back at the watercolours, the cross-hatching appears like the mesmeric lines of Agnes Martin, each individually identifiable so that we become aware of the meditative movements of the artist’s hand. It becomes clear that using a fuller brush or flowing medium would have created too opulent a feeling and would undermine the quiet, lean quality of her work.

I’ve not seen The Dance of Life in person, and have hungrily searched the internet for better photos of it (links to the best I could find below). This painting was commissioned to decorate the nurse’s canteen in the Robert Jones Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital, Gobowen near Oswestry in 1951. Following building works, it was in storage for years and has only fairly recently been restored and displayed in Glyndŵr University, Wrexham. It is made up of 6, 5-foot-tall panels covering about 46 square metres, and represents the alienation of humanity from nature.

Eldridge wrote of the panels, “I suppose in all they contained almost every good idea that I had ever had till then.”[4] The first panel reworks a theme she explored in the piece which won her the prestigious Prix de Rome travel scholarship in her early career: telling the bees. This is a Europe-wide tradition of informing a household’s bees of major events, usually a death, but sometimes also a marriage or birth, or facing abandonment of the hives. The rural scene with multiple female figures dominating it is reminiscent of several of the pieces she produced in Italy, reproductions of which are visible on the Abbott and Holder website.[5]

The other panels range from a relatively straightforward scene of the rotting skeleton of a boat sharing a beach with golden plovers, entitled The Beauty of Natural Decay, to trippy scenes of preachers calling from lobster pots, children playing with marbles and holding hands with a monkey, a human skeleton haunting a group of singing boys, a pair of howling figures seemingly referencing Masaccio’s expulsion from the garden of Eden, and people being bombarded, not with bombs from the planes and blimps visible in one of the panels, but with paper, representing the evil of the printed word. Looking at it you career from easy-viewing naturalistic scenes of rural life to nightmare worlds of violence and mystery. It is controlled and disorientating, beautiful and jarring, moralistic and questioning.

Where did this vision come from?

In her early career she was a big deal. She was praised in The Times, Observer, The Daily Mail and many more publications. Her RA exhibits were “all sold as soon as they were hung.”[6] Something which makes me laugh is the way that pretty much every account of her life I’ve read has mentioned one significant purchase from her early career. Ladies and gentlemen, Elsi Eldridge owned an OPEN-TOPPED BENTLEY. This is generally used to mark her metropolitan sophistication, and ability to make serious money from her painting. As I mentioned, she won the prestigious Prix de Rome when she graduated from the RCA, and spent time in Italy painting agricultural scenes, before returning to paint a mural in a school, (coincidentally at the top of my road, and where I’m planning to be married after lockdown is lifted).

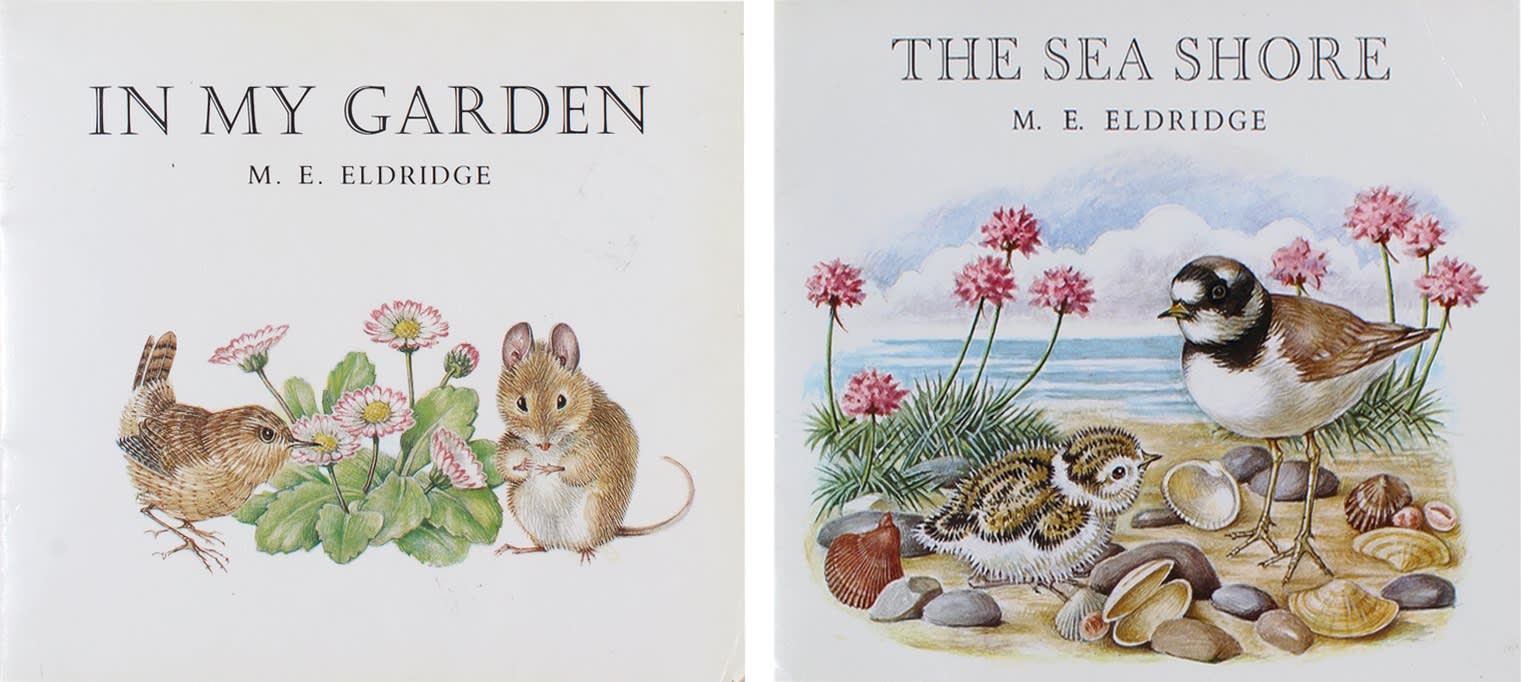

Two children’s books by Eldridge

A photo of her from that era has, as Professor Jason Walford Davies (of the R.S. Thomas research Centre in Bangor University) points out, the look of Greta Garbo. On having her sell-out first solo show at Beaux Art Gallery, Bond Street, in 1937 she vowed never to have another. Unlike many people who make such exclamations, she followed through. She became an art teacher in Oswestry then Chirk, where she met and married Thomas. Her marriage to Thomas meant living in various isolated rectories around Wales, far from London where an artistic career had been opening.

Was Eldridge, shrinking from life as a ‘successful’ London career artist, in favour of being a parson’s wife in the country? Was this just a practical move of someone who needed a job, as Professor Tony Brown suggests, and who then fell in love? Or was this the best thing for her art? There is a tone of bafflement in a lot of the writing about her – why did she leave London? Rogers calls it “a mystery.” Her son Gwidion says, “There was always a certain withdrawal-from-the-world tendency in my mother. She did go into a nunnery once, though she got out again pretty quick. But she was young and pretty, and, from her various hints, I think the flight to Chirk may have been a reaction against the casting-couch tendency in the art world.”[7] There was an unwanted proposal in a blackberry bush from painter Vincent Lines, early on which might have contributed to her ‘flight’: “A thorny place and a thorny problem,” she wrote, “I had to sadden him for who could marry a person whose work one did not admire, and whose hands steamed in the cold weather?”[8]

Whether her marriage was good for her work is another subject for discussion amongst those interested in either her or R.S. Professors Brown and Walford Davies, in their fascinating joint lecture (available on YouTube)[9] about the couple, present the silence in their house, as less that of sad and chilly distance, than of companionable asceticism. Eldridge certainly influenced R.S.’s poetry, introducing him to the work of many writers, hauling him into the twentieth century and inspiring an enormous change from his old-fashioned, romantic juvenilia. “He’d met a brain,” their son commented, “a slightly bizarre brain, but well read, much more so than him in the early days.”[10]

But it was an unequal companionship. The rhythm of her output was, unlike that of R.S., sporadic. Art historian Peter Lord commented, “Nothing grows in the shadow of a tall tree.” Philip Athill of Abbott and Holder is quoted by Rogers, asking the pertinent question, “Did R.S. Thomas wash up? If he did, then the matter of her subsequent career is still a mystery. If he didn’t, then there’s the simple answer. If you look at a list of early twentieth-century prizewinners at the Slade you will find all these women’s names. And what became of them? They just disappeared into domesticity.”[11]

Their shared politics are visible in her work, particularly explicitly in The Dance of Life, a piece she could not have made in London, or indeed anywhere but Wales, or from any life but hers. The Thomases may not have been feminists (eco- or otherwise), but they were politically radical. R.S. got into trouble with the Church for writing to the newspaper, calling all men of God to oppose the Second World War. ‘The Machine’ was the monster against which they railed, he sometimes specifically preaching about “the evils of fridges”, she ripping out their ugly central heating from a freezing old house. They knew that humans were damaging the world through industrialization. And the complexity of works like The Dance of Life along with the intense focus of her nature studies show that Eldridge was not a simplistic thinker on the matter, but someone who dedicated her significant talent and power of concentration on it.

Three postcards from Medici by Eldridge

Although Trant’s labelling of her as ‘eco-feminist’ continues not to sit right with me, Eldridge’s insight into the interrelations of human power structures and the natural world are hauntingly prescient, and would reward examination through an eco-feminist lens. Having read so much about her over the last few weeks, I can’t wait to be able to get back into the collection and revisit her beautiful nature studies there, knowing of what else, what uncanny wanderings in paint, this inquisitive anatomist was capable.

[1] Carolyn Trant, Voyaging Out: British Women Artists from Suffrage to the Sixties, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019), p.63

[2] Byron Rogers, The Man Who Went into the West: The Life of R.S.Thomas, (London: Aurum Press, 2007), p.140

[3] Photos visible here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/glyndwruniversity/sets/72157625399291630/

[4] https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/health/hospital-mural-dances-back-life-1885751

[5] I’d particularly draw your attention to Poggio Gherardo, Settignano and Women preparing for the olive harvest, Umbria.

[6] Rogers, p.106

[7] Byron Rogers, p. 106

[8] Rogers, p. 108

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fv1Q4Y625fE

[10] Rogers, p.42

[11] Rogers, p. 111

Many thanks for your guidance:

Philip Athill

Tony Brown

Christopher Campbell-Howes

Paul Liss

Bibliography and Links

Images of The Dance of Life:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/glyndwruniversity/sets/72157625399291630/

Lecture by Professors Tony Brown and Jason Walford Davies on Eldridge and R.S. Thomas:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fv1Q4Y625fE

Abbott and Holder Eldridge Exhibition:

http://www.abbottandholder-thelist.co.uk/mildred-eldridge-exhibition-2017/

Entry in Dictionary of Welsh Biography:

https://biography.wales/article/s12-ELDR-ELS-1909?&query=*&searchType=nameSearch&lang[]=en&author_multi_facet[]=tbr%%en=Tony%20Brown%%cy=Tony%20Brown&sort=sort_name&order=asc&rows=12&page=1

Wales Online

https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/health/hospital-mural-dances-back-life-1885751

BBC

https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/wales/entries/08b7a712-10cf-3a8d-bf48-a6d81eed01d0

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-wales-29234645/celebration-of-mildred-elsi-eldridge-artist-wife-of-rs-thomas

Glyndwr University

https://www.glyndwr.ac.uk/en/AboutGlyndwrUniversity/Newsandmediacentre/Latestnews/News/CelebratedartistslifestorytobetoldwithhelpfromWrexhamGlyndwrUniversity/

Tish Farrell Blog

https://tishfarrell.com/2014/06/25/yesterdays-shining-star-the-restoring-of-artist-mildred-elsi-eldridge-1909-1991/

Books:

M.E. Eldridge, The Sea Shore, (London: The Medici Society, 1986)

M.E. Eldridge, The Sea Shore, (London: The Medici Society, 1983)

Simon Fenwick and Greg Smith, The Business of Watercolour: A Guide to the Archives of the Royal Watercolour Society, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997)

Byron Rogers, The Man Who Went into the West: The Life of R.S.Thomas, (London: Aurum Press, 2007)

Michael Spender, The Glory of Watercolour: The Royal Watercolour Society Diploma Collection, (Newton Abbot, London: David and Charles, 1987)

Carolyn Trant, Voyaging Out: British Women Artists from Suffrage to the Sixties, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019)

More like this on the Blog...

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Robert Hills (1769-1844)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Helen Allingham (1848-1926)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Read: Bodies in the Archive: Is There an Alternative History of Watercolour?