This week from the RWS Archive Edith is bringing you a closer look at the work of Helen Allingham (1848-1926), the first female member of the RWS. Allingham is known for her 'pretty' watercolours of rustic English cottages - the question is: is 'pretty' good?

When I told my grandmother I was writing about Helen Allingham, she remembered her immediately: “Ah yes, pretty pictures.” Exactly. Initially, Allingham seems easily categorizable: Victorian lady watercolourist of rustic English cottages. The scenes are idealized, verging on sentimental, soothing, sometimes beautiful, always pretty. Under scrutiny, she gets harder to pigeonhole, operating on three main levels: as documentarian of a disappearing way of life; as romanticising fantasist; and as a female artist.

Many of Allingham’s contemporaries were keen protectors of rural life in response to industrialisation. For example, William Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877, and Octavia Hill set up the National Trust in 1895. In this context, Allingham’s fine paintings, detailing even irregularities in brickwork, could be attempts to document endangered vernacular architecture. Annabel Watts has done an impressive survey of cottages painted by Allingham, comparing them to her own photographs, and those by Allingham’s friend Gertrude Jekyll.[1] As such, the paintings are fascinating contributions to local and social history.

But to treat them as simple documents would be wrong. Allingham’s biographer, Ina Taylor, writes, “Those cottages which Helen believed had once possessed thatched roofs, she ‘re-thatched’ in her paintings… Similarly if she detected any evidence that a cottage had originally had diamond-lattice window panes, these would be ‘restored’ (she kept an old window frame in her studio to copy).”[2] Out buildings, neighbouring houses, church towers, were all treated with artistic licence: some removed to emulate history as Allingham envisioned it, some for design purposes. Cottages lifted from villages appear isolated, embraced by nature in a manner “comforting and not threatening, whether wild or cultivated”[3].

Helen Allingham, Feeding the Fowls, Pinner, RWS Collection

Instead of painting the occupants, she hired London models, dressing them in old-fashioned clothes she kept for the purpose. The women are beautiful, the children cherubic. Old people feature only rarely as benign onlookers, and men are almost entirely absent.

Poverty is prettified in a middleclass vision of the rural working class. Tennyson, Allingham’s friend and ally in finding paintable cottages, reputedly refused to repair his gardener’s cottage, despite its derelict state, because it was ‘picturesque’.[4] Allingham’s own desire to ignore anything troubling is illustrated by her neglect of her daughter Evey whose mental disability Allingham, “found hard to accept and which eventually alienated her from the girl.”[5]

Allingham painted Irish cottages during an 1891 visit. Poverty is more evident in these scenes, but the barefoot woman with bucket and pitcher in hand, is still a healthy-looking classical beauty in the prime of life. If she sought to document architecture, she ignored politics. Harry Johns Thaddeus shows what an Irish cottage scene might look like from the other side of the door and the class divide, in An Eviction Scene, County Galway, 1889.

But in an alienating world of urbanization and colonialism, the anchoring comfort of an Allingham rustic idyll might not be a trivial decoration, but a profound link to a lost sense of home and England.

Her art career in an age when women were discouraged from such lives is impressive. The oldest of seven, she was a teenager when her father and three-year-old sister died of diphtheria, and she adopted a lifelong financial responsibility for her family. She illustrated Graphic magazine in her early career, and later painted scenes which would sell, supporting her family. Part of Allingham’s skill was in painting something that people would allow, encourage and pay her to paint: their power is in their prettiness. Watercolour was derided at the RA schools where she studied. It was considered a lesser medium to oil, an amateur’s and a woman’s paint. Instead of attempting to emulate men, she learnt to excel in this ‘feminine’ art.

Although she was not as pioneering as her extraordinary aunt Laura Herford (who tricked the RA school into accepting her as the first female member), Allingham’s determined pursuit of an artistic career blazed a trail whether she intended it or not. The RWS now has a female president 130 years after Allingham was elected first female member.

Allingham created a domestic, feminine world in her paintings, rarely showing industry. Among her many pictures of Kent, for example, oast houses, which are surely as beautiful and interesting as cottages, are absent. A typical scene outside a cottage is in daylight, ensuring men of working age are legitimately absent. Women and children stare shyly at us from the gateway of the abundant garden. The isolated house is not complicated by the hustle and bustle of village life. Its isolation focuses our minds on the family unit, and the female role within this ideal home.

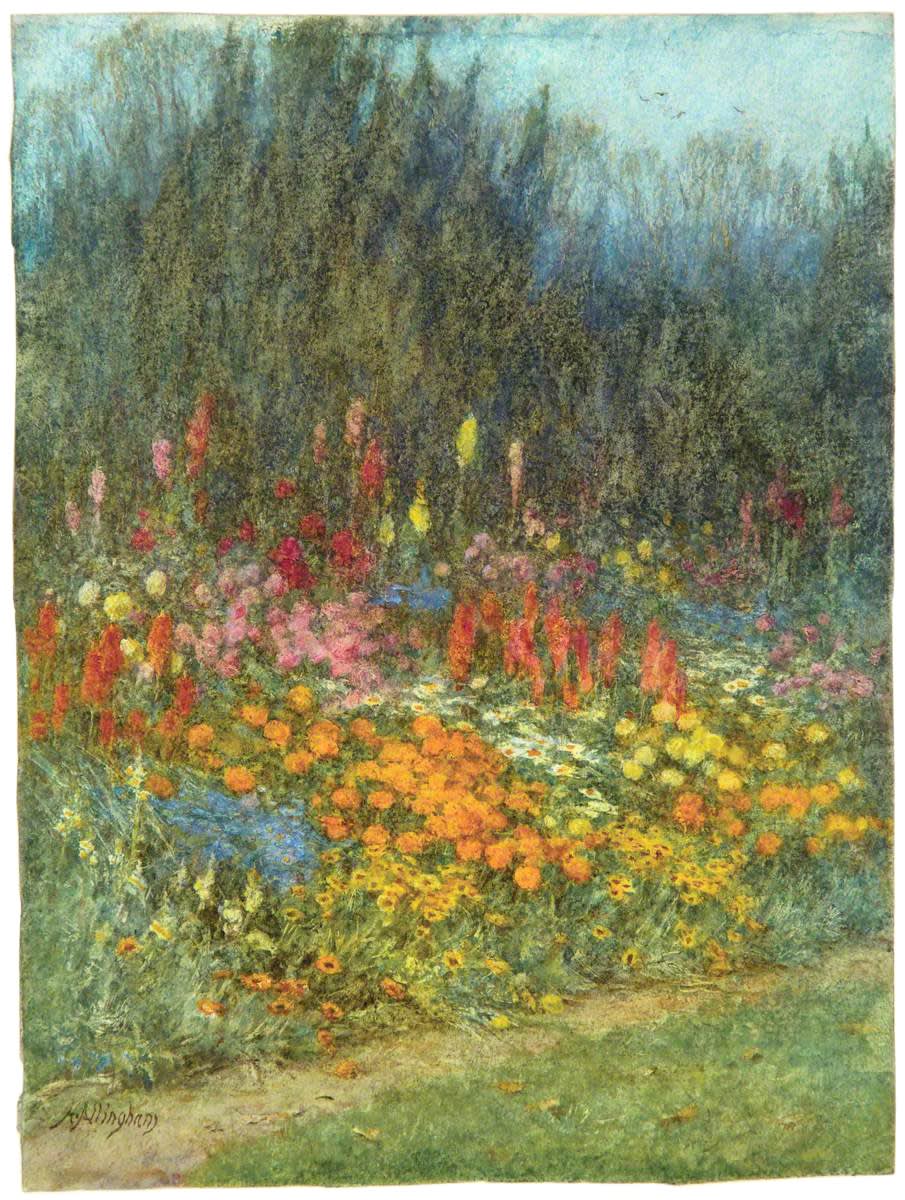

Helen Allingham, A Bit of Autumn Border, RWS Collection

The cottage garden provides a place where nature and femininity can be unthreateningly abundant. The walled garden has symbolized Mary’s virginity in art since medieval times. These women, with a near-Marian aura of ideal motherhood, stand in the cottage garden, open gate inviting us to enter the fantasy.

The road cuts across our communion with the woman in the cottage, a reminder of machinery, modernity and movement. (Watts complains of the difficulty of photographing houses with cars parked outside.) But for a moment, we were caught in the static world of rustic nostalgia where women, appropriately contained, nurtured and nurturing, could, like their gardens, thrive beautifully and bountifully.

While this ideal is hardly feminist, the fact that a woman was making her career selling the fantasy, complicates it. To me it is an example of the many ways in which women have used the apparatus of their servitude to make active, self-sufficient and fulfilling lives. While these pictures document vernacular architecture, perhaps the nostalgia for an imagined England is a more useful document of what it was like to be a Victorian. And the fact that a woman was able to make a living from selling them is a powerful reminder of what the world was moving towards, as well as what it was moving away from.

[1] Annabel Watts, Helen Allingham’s Cottage Homes Revisited, (Surrey: Books for Dillons Only, 1994)

[2] Ina Taylor, Helen Allingham’s England, (London: Caxton Editions, 2000)

[3] Pamela Gerrish Nunn, ‘The Cottage Paradise’, Victorian Review, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring 2010), pp. 185-202

[4] Taylor, p. 68

[5] Taylor, p. 50

Selected Bibliography

Fintan Cullen, ‘Marketing National Sentiment: Lantern Slides of Evictions in Late Nineteenth-Century Ireland’, History Workshop Journal, No. 54 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 162-179

Simon Fenwick, The Enchanted River: Two Hundred Years of the Royal Watercolour Society, (Bristol: Sansom & Company, 2004)

Pamela Gerrish Nunn, ‘The Cottage Paradise’, Victorian Review, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring 2010), pp. 185-202

Ina Taylor, Helen Allingham’s England, (London: Caxton Editions, 2000)

Annabel Watts, Helen Allingham’s Cottage Homes Revisited, (Surrey: Books for Dillons Only, 1994)

More like this on the Blog...

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Robert Hills (1769-1844)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Mildred Elsi Eldridge (1909-1991)

Read: Bodies in the Archive: Is There an Alternative History of Watercolour?