The third artist in our International Women's Day series is Julia Midgley RE. Julia's practice focuses on medicine, archaeology and conflict, inspired by the British war art tradition. Reportage commissions have found Julia surrounded by Vikings at Blackpool Pleasure Beach; working in archaeological trenches at Stonehenge; and drawing in surgical operating theatres (to name a few!)

Interview: Matilda Barratt in conversation with Julia Midgley RWS RE.

You describe yourself as a ‘documentary artist’ – what do you mean by this?

A Documentary artist is also referred to as a Reportage artist, ie someone who draws what they see as events take place before them. This is very much in the war artist tradition, a genre which fits securely within the British tradition of sending artists to war zones. The artist acts as a fly on the wall, using a pencil or pen instead of a camera. For me I use pen and ink, pencil, and/or watercolour wash, on a variety of papers, some tinted, some cheap, some handmade. The choice of paper is the first and most important decision for me. It should reflect the background, for example a clinical situation or a dark space short of light. I use a fishing backpack with integral stool when working on location. This gives me all I need, it contains my materials and provides a seat, is portable and neat.

A documentary artist’s strength, and vocabulary, is the drawn line, it bridges the barriers of language. My own practice focusses on medicine, archaeology, and conflict, it has perhaps been inspired by the genre itself, war artists past and present.

In Drawing Lives – Reportage at Work, when discussing the role of drawing as documentation, you stated that “drawing is not in competition with photography, it offers an alternative view”. Could you expand upon this?

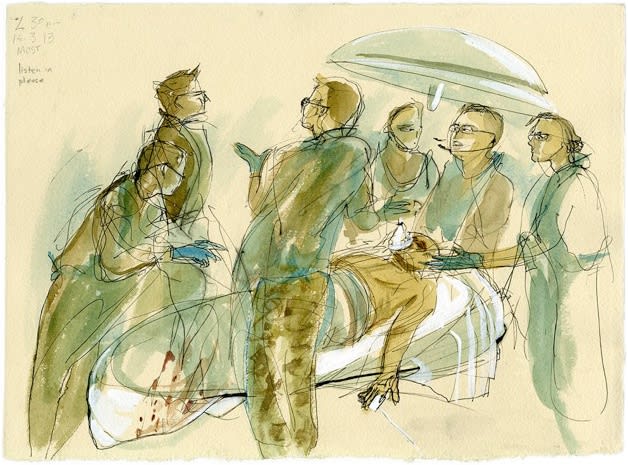

I often record minutes and hours in one drawing. A figure may appear several times in one drawing, illustrating the passage of time. A camera can only record fractions of a second. One is not better than the other they are complimentary and offer different interpretations of a given situation.

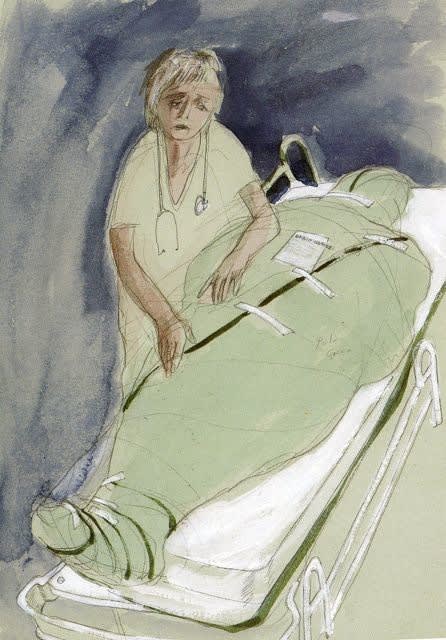

Thanks to the minimally invasive nature of a pencil working on paper an artist is readily tolerated, particularly in arenas of sensitivity such as surgery or disaster. This is particularly true with regard to military medicine where for many reasons photography is highly restricted.

Sometimes, for example in a medical situation, patient confidentiality must be taken into account. Drawings are seen as less likely to compromise this, but, more importantly from the patient point of view an artist sitting quietly at the bedside is deemed a non-invasive presence, indeed sometimes a welcome diversion.

What would you say of the role of drawing across multiple disciplines, particularly to someone who believed that drawing were irrelevant to the worlds of science, medicine, archaeology and so on…?

Well the discipline of drawing is essential for enhancing observation, hand eye coordination and for honing the art of composition. This could be a graphic designer composing a poster layout, a Fine Artist designing a website and so on...

In the 21st Century we are bombarded by photographic imagery, in a time where Photoshop is used universally to ‘doctor’ images, drawings interestingly are becoming a more reliable witness.

An artist edits as they work, irrelevant backgrounds are easily left out, whilst important elements can be emphasised with strength of line. In a gallery of portraits those which are drawn can capture attention amidst photographic portrayals. This is because film and photography are everywhere, TV, phones, news media, cinema...

As one of a group of artists working alongside archaeologists some years ago at Stonehenge the two groups of professionals developed a mutual respect. We all used drawing to document what we saw but with different ends in mind. The archaeologists had to draw with meticulous accuracy, choosing even in the 21st Century to use the human eye and hand for their precise surveys. The artists were there to record and respond to archaeologists at work with greater freedom to interpret their observations.

Reportage has led you to work in a variety of different places, with commissions often taking the form of residencies lasting anywhere between one day to two years! Whilst I imagine it is impossible to narrow it down, are there any commissions in particular that have really stuck with you, or any that you could point to as having been especially influential to your work and life?

Medicine and war art have always been a driving interest. In 1997 I began a two year residency at the Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospital Trust. The incredible access I was accorded at the time enabled a complete picture to be drawn (literally) of the art and science of modern medicine as practised at the end of the 20th Century. Undoubtedly the project had a huge impact on me, reinforcing my interest and engagement with medical subject matter; the humanity revealed by staff and patients; the physiology observed in operating theatres and the staff working out of sight in hospital laundries and research laboratories, they all featured in the resultant portfolio. This project and the project publication were key in introducing me to the Royal College of Surgeons of England. This in turn proved pivotal when discussing the War Art and Surgery project some years later which recorded the training of military medical personnel pre deployment to Afghanistan, and the rehabilitation of wounded soldiers after their return to the UK.

When did you get elected to the Royal Watercolour Society and why did you decide to join?

I was elected in 2017. I had been a Fellow of the R.E. for some years and whilst printmaking is an important part of my practice watercolour is integral to all the work I do in the studio. This is particularly the case with regard to my documentary work. Watercolour enables rapid mark making, is subtle, and delicate, its quick drying properties and its immediacy render it an indispensable part of my toolkit. Reportage work is not often displayed in Galleries but I have always been keen to exhibit the drawings in venues other than those connected to my projects. I felt the genre should have an exhibiting outlet. Bankside Gallery and the RWS were familiar to me and I hoped could be a perfect fit for Reportage. My application as a reportage/ documentary artist must have been an unusual one for the Society and I am in their debt for electing me and affording a “shop window” for my drawings.

What would your advice be to a young aspiring artist?

To accept that they will need to have another job, to be prepared to work all hours of the day; and not to expect people to come knocking on your studio door.

Draw all the time, keep sketchbooks, promote yourself, enter competitions, be aware of the industry and embrace more than one medium. Versatility is good and useful.

Given all of the above its a great thing to be an artist. A career as a visual artist guarantees variety, inventiveness, an introduction to a world populated by stimulating colleagues, people and places. It's a demanding rewarding and privileged way of life.

More like this on the Blog...

Read: International Women's Day Series: Gertie Young

Read: International Women's Day Series: Jill Leman

Read: International Women's Day Series: Nana Shiomi

Read: International Women's Day Series: Rachel Gracey

Read: International Women's Day Series Sally McLaren