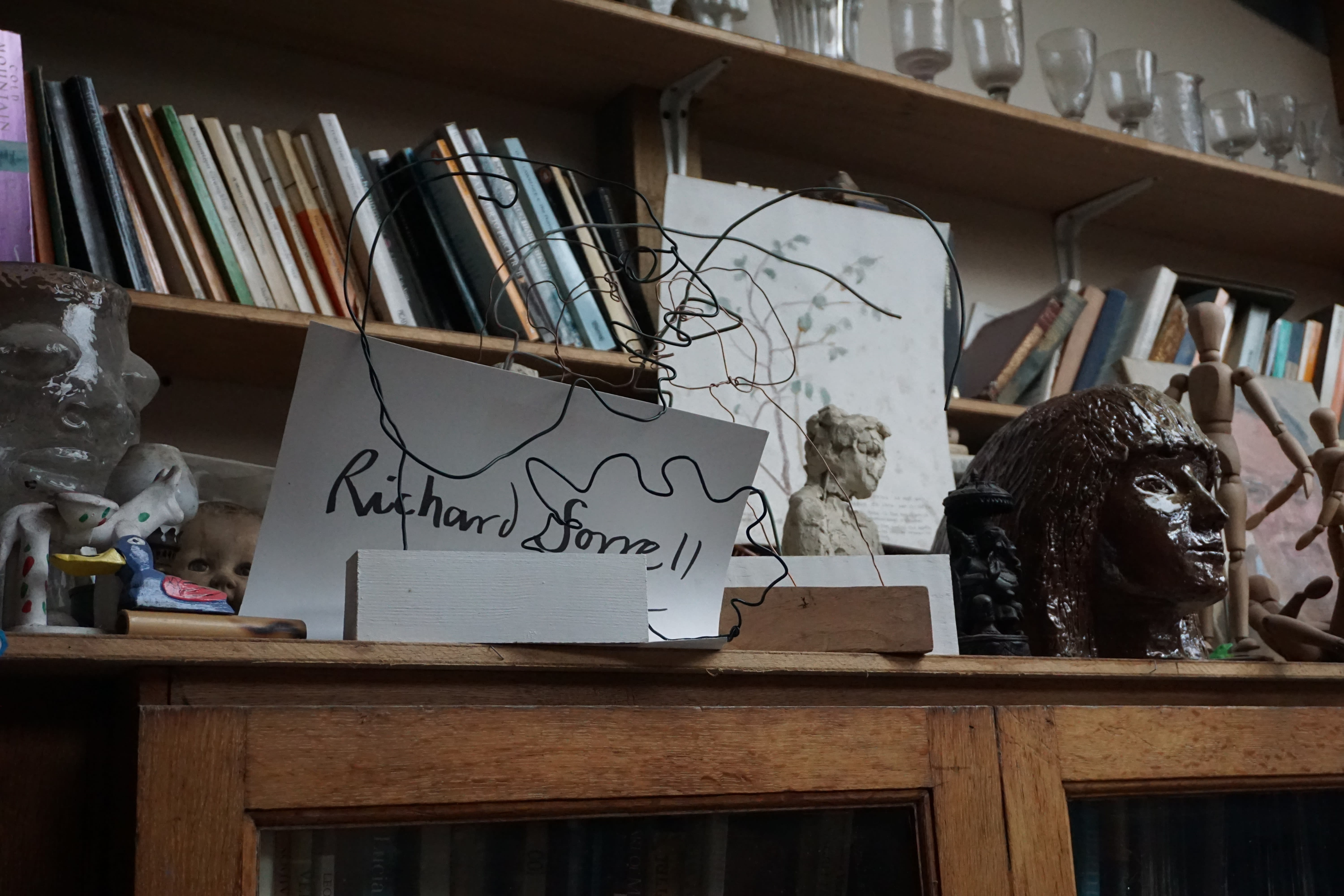

Ahead of his solo exhibition at Bankside Gallery this summer Bankside Gallery’s Fay Brown visited Richard Sorrell at his studio near Penzance to ask him a few questions.

When did you join the RWS? And what appealed to you about joining this society?

I joined the RWS in 1975 when I was 27, the year after my father died. He had been elected in 1935, I think. My mother was also a Member. I had recently completed my training at the Royal Academy Schools. As a child, I had been taken along to the artists’ lunches on ‘Varnishing days’ at the galleries in Conduit Street. There I met a great many well known artists: WH Freeth, R Vivian Pitchforth, Robert Austin and Ethelbert White, whose wife loudly complained about my mother’s sardine sandwiches. It seemed a great idea to try and become an RWS Associate, and I was greatly honoured when this happened.

How did you find your time as President and what made you want to take on this role?

By 2006 I had been a Member for a long time, and the Society had been good for me and helped my career a great deal. I felt that I’d like to try and repay this kindness. The RWS is a good thing for a young person to belong to. It gives a place to exhibit regularly – something they may not already have, and it provides contact with eminent artists. So during my time as President I encouraged young people to join. I was also very keen to emphasise that the RWS is a forward looking and outward looking society. I encouraged links with other watercolour societies in Britain and around the world, tried to establish friends groups and set up the website.

Your working style seems to have changed quite a bit over the years, was this intentional or did it happen naturally?

Though I have always been interested in invented images, for the first part of my career I made a living mostly from landscape, portrait and still life painting. As a student I felt that life drawing, which is intended to be difficult was something that I should persevere with. It was a very long time before I made the subconscious link between this discipline and my own painting. I found that I could remember how things looked – for instance, I could paint things that I had dreamed about. Early on I painted a man feeding some birds from memory. Pictures like these turned out differently from those painted directly from life. I came to categorise them in my mind as ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ paintings. Objective means ‘copying’ nature, where one tries to render an object or a view as faithfully as possible, concentrating on form, colour and the effect of light. With subjective painting the most important thing is the image, its layers of meaning, integrated with the structure of the picture. Plenty of painters can paint pretty proficiently things that they see in front of them, but only I can paint what I imagine. In 1990 I had a show at Agnews and I tried to decide whether it should be an exhibition of city views (which I was fairly good at) or of imaginative work. I went with imaginative, and I think this was a turning point, and since then I have concentrated largely on inventions and pictures from my imagination.

Talk us through your working process. Can you explain a little about the techniques you use in your work?

I’ll tell you a bit about the process behind my painting ‘ The Ancient Days’. This is a painting about nature and going back to nature. I have a print by the great Japanese printmaker Utamaro, which I value for its beautiful drawing. It is called ‘Yannuba holding chestnuts with Kintaro’, and it shows a graceful lady with some prickly chestnuts bending over a little boy. Utamaro indicates that she is a wild woman by giving her long flowing hair. My picture also shows a wild elemental woman with her son. This woman is a Mother Nature figure, and they have come to a wild rugged place, and in the distance is a glimpse of the ocean. But this place isn’t primeval; it has returned to the wild, and cultivated plants like a peony and a tree lupin are growing there. Behind them is an eleagnus hedge. This is the imagery of the picture. I worked on it for a long time. I was concerned with the proportions of the figures, the structure of the composition (near diagonals enclosed in a square) and by the movement in the leaves behind. The woman’s face and posture derive from ancient Egyptian ideals; only her left leg is modern. If she stood up she would be a gigantic figure!

People’s interactions are themes reccurring in your work. What is it about people’s behaviour that inspires you to paint them?

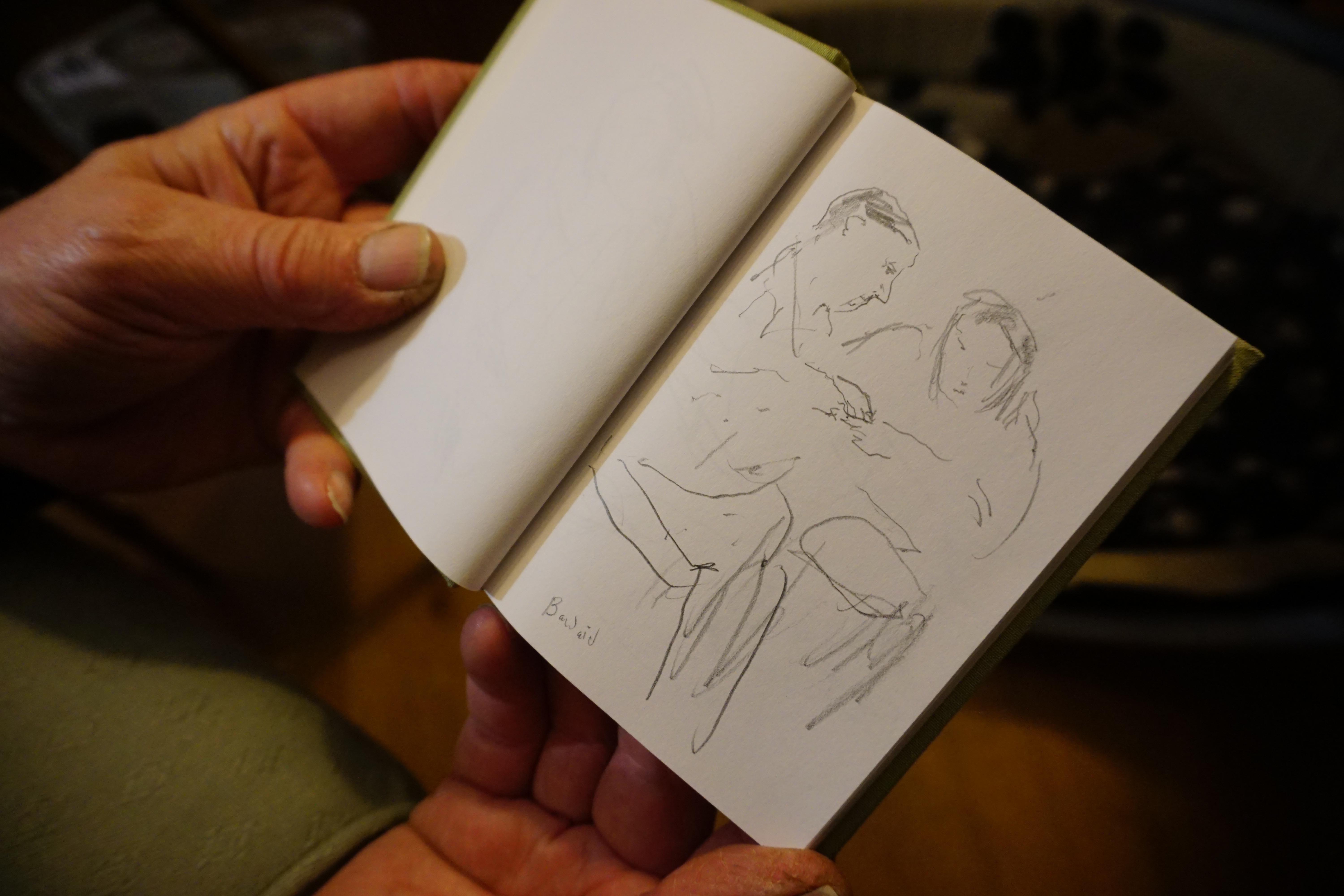

I am intrigued by relationships between people. Sometimes I note interesting incidents in my sketchbook, and sometimes these lead to paintings. The other day on a visit to London, I was sitting on the tube next to my son Edmund. Opposite I saw a man putting a plaster on his girlfriend’s finger. How caring, I thought, and I scribbled a note of it in my book. ‘Did you see that?’ I asked Edmund. ‘No, I didn’t notice anything’, he said.

Your solo show in 2018 is based around the theme of Brexit. Can you tell us a little more about what to expect from the show?

I was very shocked by the outcome of the EU Referendum. The great European experiment had, it seemed to me, started to realise the age old dream of reaching out to embrace all the people of Europe, and it had done this, most significantly, through peaceful means. Despite all of the EU’s shortcomings, this is a fine aspiration. The EU allows and encourages freedom and expanded horizons. We need to be more united to be more free. Some people feel as emotionally opposed to the EU as others feel in its favour, and this has opened up awful divisions in our society. I wanted to use my painting to reflect on these violent interactions. There are a number of paintings in this show based around a big picture, ‘Brexit Camp’. This is an angry painting about the arguments leading up to the Referendum. Two men argue about the benefits of leaving the EU. The woman in yellow indignantly takes up the dispute, whilst the other carelessly goes along with whatever is said. A cynical manipulator stands on the right, whilst a group of young people, who will inherit the situation, trudge along the shore. Another small painting shows two naked people stranded on a lonely rock in the sea.

Tell us a bit about the book you’re working on. What made you want to do a book? Is narrative something you’d like to explore further?

The book is called ‘After Mostly, A Story of Downsizing’. It is a picture book that started off as a series of images and texts on my tablet, where I store images of my pictures. I selected pictures and put texts with them, and the pictures adopted temporary new meanings. The story evolved into a riches-to-rags tale. Roy and Joy move from their ‘tiresome’ luxurious living to a humble cottage in a village. They are tricked into leaving it and by degrees (each step of which seems to be an improvement) they lose everything. The story reflects Voltaire’s Candide where each downward step is seen as ‘all for the best in the best of all possible worlds’, and is my vision of the result of Brexit. I redrew the pictures in ink and watercolour and the whole thing was redesigned to make a book.This exhibition takes the book as its focus, with original paintings from which the drawings derived, and paintings inspired by the book are shown along with related drawings, paintings and small sculptures.

How does living and working near St Ives inspire your work?

We came to live at Higher Hellangove permanently in 2009, though we had bought it some years before. The house looks out over Mounts Bay with views from Penzance and Newlyn to the Lizard. It is a spectacular view, but my studio is enclosed with curtains drawn closed and lit by rooflights, and I concentrate on internal ideas. My pictures are filled with people, but we have few passers-by on our windy hillside. The sea, which is a powerful presence here, has become more of an element in my paintings. Outside I have planted hundreds of trees and started to develop extensive gardens.

How does working in a variety of mediums affect the way you work and which medium do you enjoy most – oil, watercolour, or mixed media?

I find it difficult to answer this question. I don’t particularly differentiate between mediums. What I’m concerned about is making a picture, and I use a wide range of mediums. The image is the most important thing. I suppose that I grew up with the idea of watercolour painting, and all of my paintings have a watercolour mindset at the back of them. Colours and areas of paint can be adapted by glazing or scumbling over them. Sometimes I paint thinned, pure coloured oil paint into freshly laid thicker white, in a technique borrowed from the Pre-Raphaelites. For a long time I used acrylic, which lends itself well to glazing and scumbling, because it dries so quickly. At the moment I am probably using oil paint most of the time. I’m also trying to do some 3 dimensional work. I made some small bronzes, and more recently I’ve made heads out of stoneware.

Which artists would you say have had the biggest influence on your work?

My mother told me that the first word that I spoke was ‘Gauguin’! There was a reproduction of ‘Ea Haere Ia Oe – Where are you going?’ hanging over my cot. Perhaps the art that I like the most is visionary painting – Bruegel, El Greco, Piero della Francesca. As a young man I had Samuel Palmer and Bonnard and Stanley Spencer as heroes. I owe a debt to Cezanne and Matisse. Titian’s paintings move me to tears, but then everyone loves Titian.

What have been the greatest challenges of being an artist and do you think they are different today for young emerging artists?

All of my life I have lived by painting pictures and selling them. I’m afraid to say that I think it would be nearly impossible do now what I have done. The great problem is the huge expense of property, which has escalated out of all proportion during the space of my career. I was paid £6000 for a job that took me 6 months to complete in 1976. I was able to buy a cottage in Norfolk where I lived and worked and brought up a family over the following 15 years. Today the thought of being able to buy any property from the proceeds of 6 month’s work is out of the question. It is impossibly hard. It is serious for everyone, and it is very serious for painting. Anyone who goes to an art school even with a great deal of talent will think that there are much easier ways of making a living than painting pictures, and that’s not good at all for the future of painting. I think that art societies like the RWS are great places to help,support and encourage artists to carry on producing work. Even if you’re not selling, you have somewhere to exhibit. Artists need three things: a living, shared art, a future-facing ‘tradition’ that they can work in, a secure place to work and an engaged public that will buy their work. This is really important. Painting is a language, and as in any language, what is said needs to be listened to. We need conversations rather than monologues. Selling pictures helps to shape the way you paint the next one. It’s a circular motion.

Richard Sorrell's BREXhibITion is on display at Bankside Gallery, 24 - 29 July.