Gerry Baptist RWS RE's work is fuelled by what he calls a "constant interest in what goes on in the world", alongside a fascination with human folly. His art celebrates humanity, life and love, while simultaneously lamenting our behaviour and the predicaments that we create. Born more from observations and concerns than anger, Gerry's work is direct, yet not hypercritical; his hope is that it might simply encourage the viewer to stop and think.

We couldn't wait to hear more from Gerry about his life and career, from his childhood spent in India to his time spent in the world of advertising, and even a charming anecdote of a chance encounter with Francis Bacon...

Interview: Matilda Barratt in conversation with Gerry Baptist RWS RE.

Could you start by telling us how you found you wanted to take up art?

There is no doubt my approach to life and my work came from my parents who had an unsophisticated and very simple way of living, without many barriers of what you can and cannot do. My Dad always seemed to be drawing in his room or playing the piano, so maybe I just followed his example – though I never managed to play the piano properly.

I have a memory of learning to draw joined up letters as a child, or rather just one letter, the ‘a’. I have an image of my hand holding a pencil, concentrating on trying to control it and make it draw what I wanted and attempting to keep the drawing of the letter between the lines printed on a sheet of paper.

I like to think that being lost on a sheet of paper is what it has always been about. But without those restrictive lines!

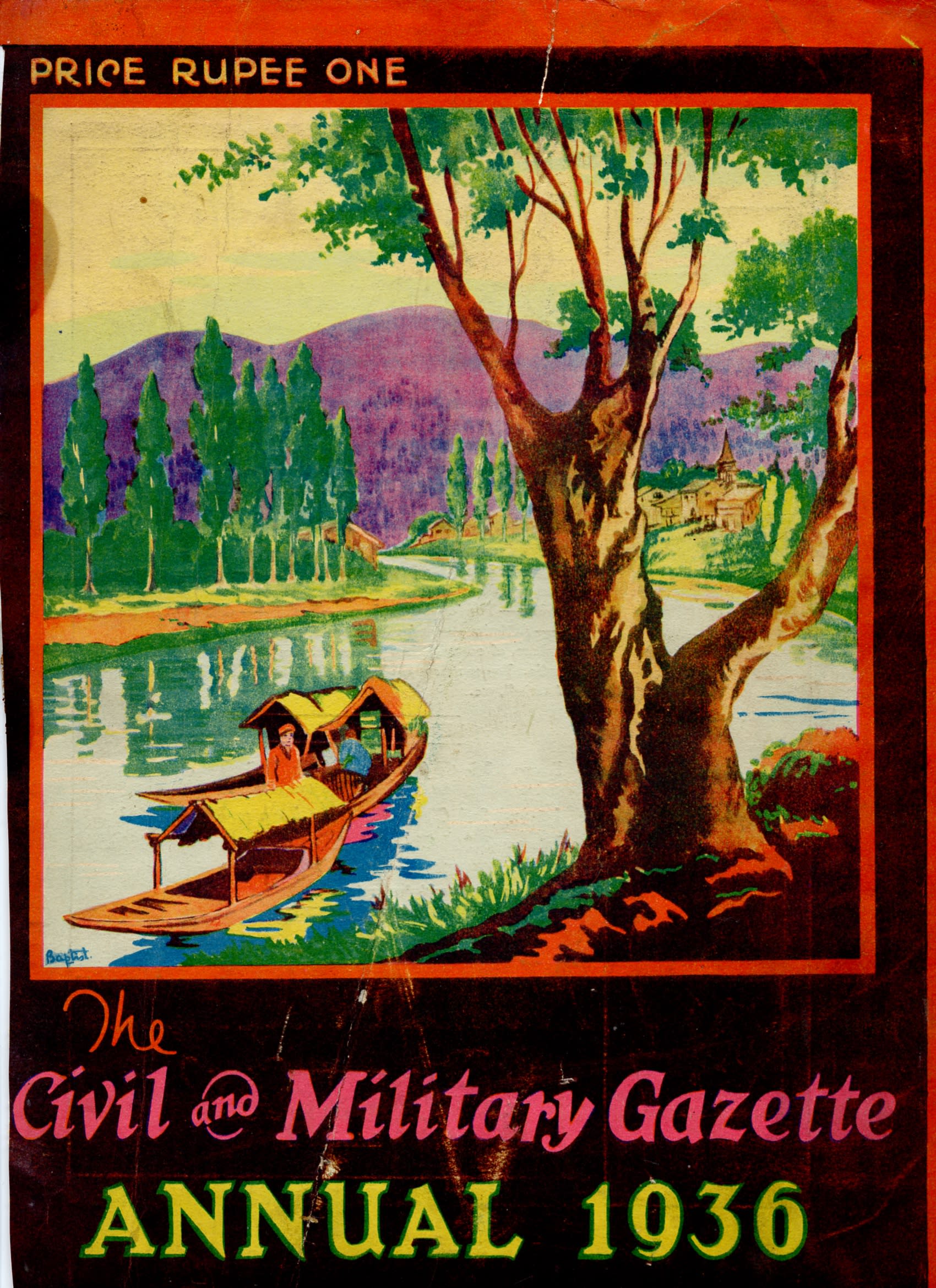

Illustration by Gerry's Father, W H Baptist

How did your experience growing up in India influence your work, if at all?

Our home was a complete mess of books, music and art. When I say mess, I do mean that: stacks of books and magazines in shelves, or on the ground – everywhere. The magazines and comics I remember were American, including Saturday Evening Post and Good Housekeeping, which were full of colour pictures, plus Superman, Katzenjammer Kids and many others which I still treasure, as well as a couple of hardbacked storybooks from the Child Development Foundation Inc., Chicago! And not forgetting that Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book was my reality! ‘It was a sort of Bohemian life,’ a friend suggested a few years back. Maybe, but it was a perfect, happy chaos that we lived in.

I remember Kolkata most. In the 1940s, it was almost a sleepy town compared to what it is today. There were even then, clanking trams and motor vans, bullock carts and cows wandering their quiet way; rickshaws and bikes and cars of all kinds. When WW2 came close to home and Kolkata was bombed, we watched Spitfires fly in just over our heads to land on what was called The Red Road. –Going to school in a Gharry – a horse drawn vehicle; the joyous relief of the monsoon rains which instantly washed away the stifling heat; walking home after choir at St John’s under the tamarind and jackfruit trees in the church grounds; the scent of the gentle, warm, glowworm-filled air is a magical memory.

These are some of the influences of India and of life at home where everything seemed perfect.

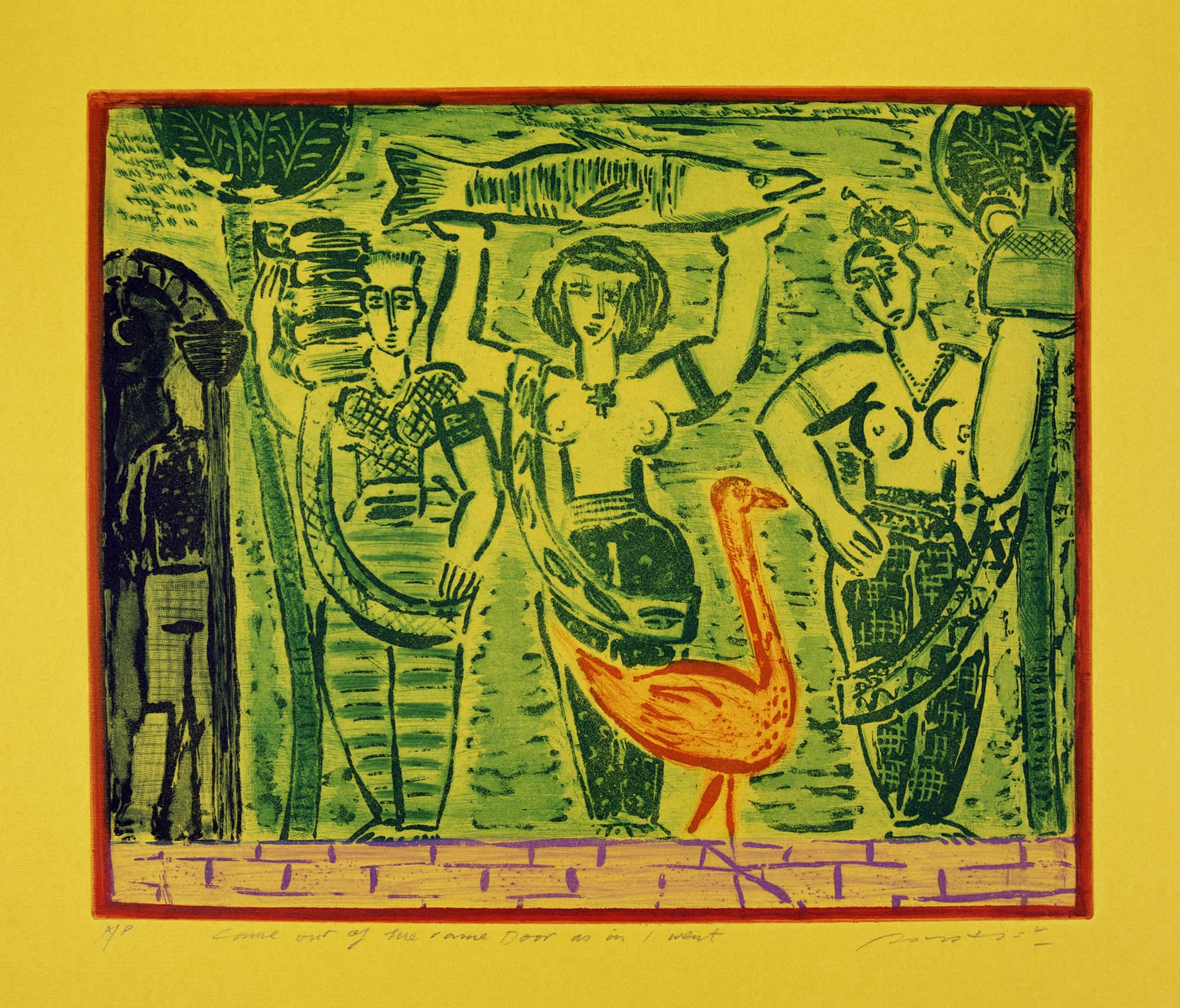

‘Came out of the same door as in I went’ Aquatint 24.5 x 30cm

From the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

What was Art School like for you?

We came to England in 1945, arriving in Liverpool on a bleak, snowy, winter day and then went to live in Essex. There were peasouper fogs – so thick that bus conductors had to walk in front of buses to guide the drivers; queues everywhere for food and biting, damp cold. I went to a state school where everything was as a school should be with bright, enthusiastic teachers and most of all, it allowed pupils, at the age of 13 to choose a main subject, which for me was art. Back then that school was attached to Walthamstow Art School in northeast London and I transferred there, aged just 16, in 1951.

The art school was excellent, with a course of general studies including life drawing, printmaking and painting. I wanted to do graphics so, after a year there, I moved to the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts, which in those days was just off Theobald’s Road in central London. There was the usual life drawing and painting but with graphics, photography and typography. It too was a very good school – one teacher who had been trained at the Bauhaus introduced us to Dada – particularly their use of typography, collage and photograms – and Duchamp, which really opened my eyes. We were very much left on our own, to learn through our own mistakes - which is one of fundaments I took away with me. In fact it was how I began to understand that an artist has to work things out themselves; it was an exciting if nerve crunching lesson for a naïve young art student to learn.

I then had to do two years’ National Service and, by the time that was over, I had no wish to go back to art school. I just wanted to get on with life.

Self portrait aged 17. Oil on paper 12 x 9”

What work did you do before you began painting and printmaking?

I just wanted to get into advertising. I really enjoyed ideas and graphics (and still do), so I began work as an art director in London in the 60s. London was buzzing, advertising was exciting: I worked with copywriters who could come up with pithy, slogans which resonated, some outrageously good photographers and excellent illustrators. It was controlled mayhem. A few years later, I was headhunted by an American agency in Germany, which added a really interesting and different way of working: the small group I was in was very philosophical, very methodical but the outcome was incredibly interesting work as within the structure they worked in, I had a sense of complete freedom. They were always interested in trying out the impossible - as we did in London. It took me time to learn there was so much poetry about the language that initially sounded so clipped. I learned so much and had a really good time and continued to work there as a freelance art director for years.

Back in London, I worked with a partner developing new products for various companies, but you were always dancing to the tune of a client. We wanted to create something of our own and it was during this time that we began to conceive a project which was to build a 21st Century version of the Great Exhibition Pavilion of 1861. A place of education and entertainment. For example we had an area devoted to the body with Terry Gilliam of Monty Python designing the fun part and Jonathan Miller the education section of that area. Other brilliant talents included David Bellamy, Patrick Moore and Arthur C Clarke. It took many years to put together. The newly conceived ‘Crystal Palace’ was huge, with seven and a half acres of glass and the building stretched 450m in length. With over 1000 acres of land purchased and planning permission consent obtained, economic viability was determined by City institutions: a consortium of 25 international banks was consequently mobilized in support. Sadly, the worldwide stock market crash of 18th October 1987, collapsed the fundraising programme resulting in the ultimate failure of the enterprise. We had done everything we could, but had to move on.

I had always painted in my free moments and it now seemed that it was time to immerse myself in ‘art’.

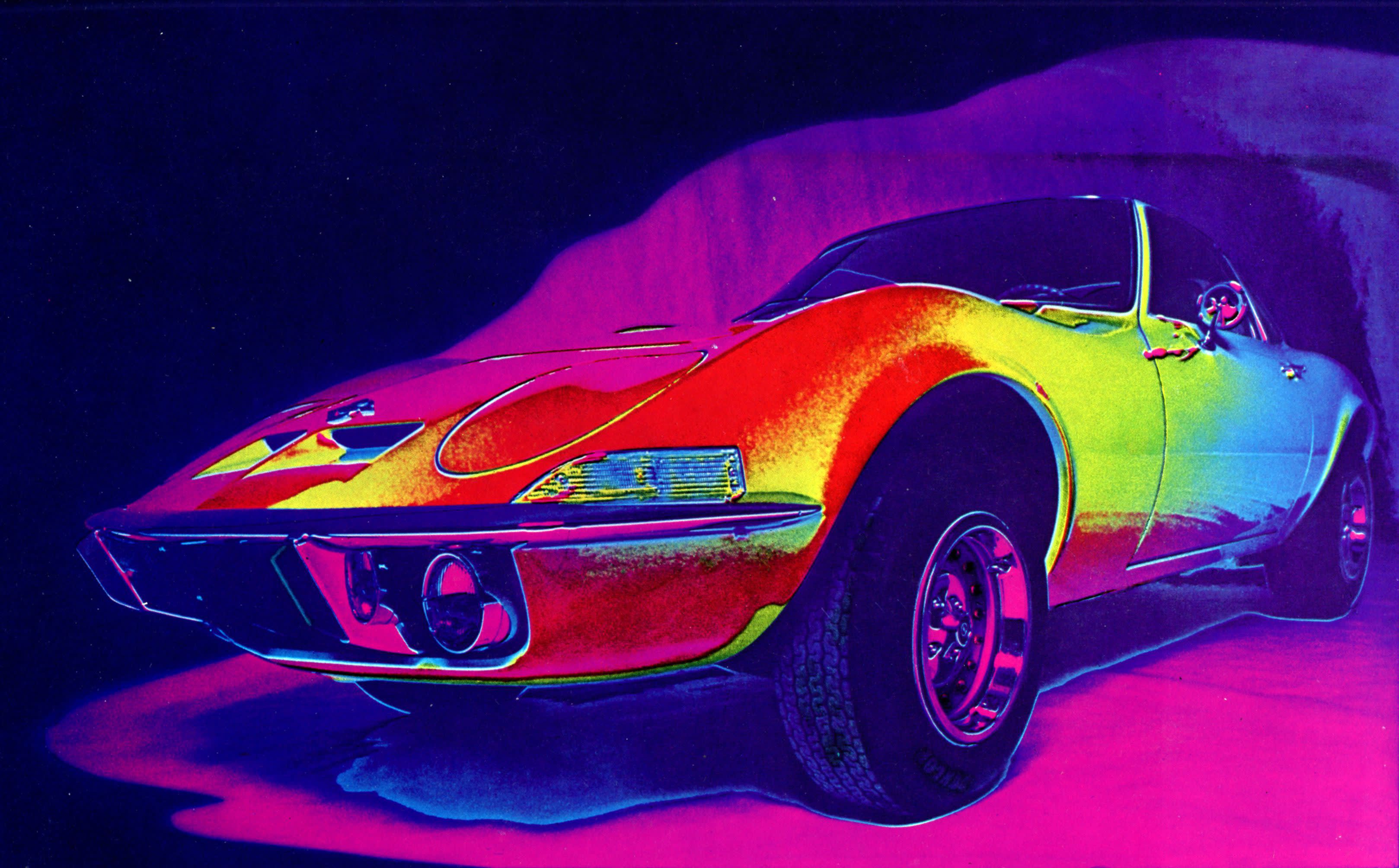

Part of a brochure for an Opel sports car

"The darkroom work which took a couple of days in 1971 to create this takes a mouse-click in Photoshop today." - Gerry Baptist

With such a comprehensive range of techniques and media under your belt, is it possible for you to point to just one medium that you enjoy most?

I couldn’t say which technique or media is more enjoyable. Using a pencil or a woodcut tool, a graphic pad or a paintbrush all have different possibilities and quite different joys. They are just ways of making pictures.

‘Engagingly, Baptist can’t say what it is that prompts him in one direction or another, or whether his mazy venturing-forth succeeds. It gives him both a detachment and a curiosity about what he makes, perhaps founded upon a breezy confidence that, with a fair wind, he may be headed elsewhere. This improvisational energy – a restless switching between the drive to do and head scratching about what exactly – adds an irrepressible exuberance to the occasional Sturm and Drang of his images and themes. In the end, he seems less concerned with communicating The Last Word on a subject than the relevance (or not) of his output to this more urgent question: what sense can I make of what’s in my head right now?’

- Extract from an article on my work by Mike Sims in Printmaking Today 2018

Which artists would you say have had the biggest influence on your work?

This is today’s quick list and in no particular order: Picasso, Goldsworthy, Emin, Bacon, Cornelia Parker, Bernini, Miro and Dubuffet.

There are artists who are able to express themselves clearly and coherently, like Michael Craig-Martin or Bridget Riley, who are well worth reading, and Picasso had such an ability to make simple, enlightening and sometimes playful comments. But it is not only artists: there are many philosophers and critics too who have the ability to delve into the mind of an artist and are able to make an explanation of the unexplained.

Whether it is influence or just sheer enjoyment of their work, I really don’t care. I have loved and stolen thoughts here, there and everywhere.

‘Six characters in search of Pirandello’ Acrylic painting. 56 x 76cm

Banner outside Bankside Gallery, London

Is experimentation a big part of your practice? Do you typically have an idea in mind of what you would like to create before you embark on your next project?

Experimentation is what I do most of the time – it is part of me. I try things out which scramble around in my head for attention. I just play and work and then eventually find out what I have done.

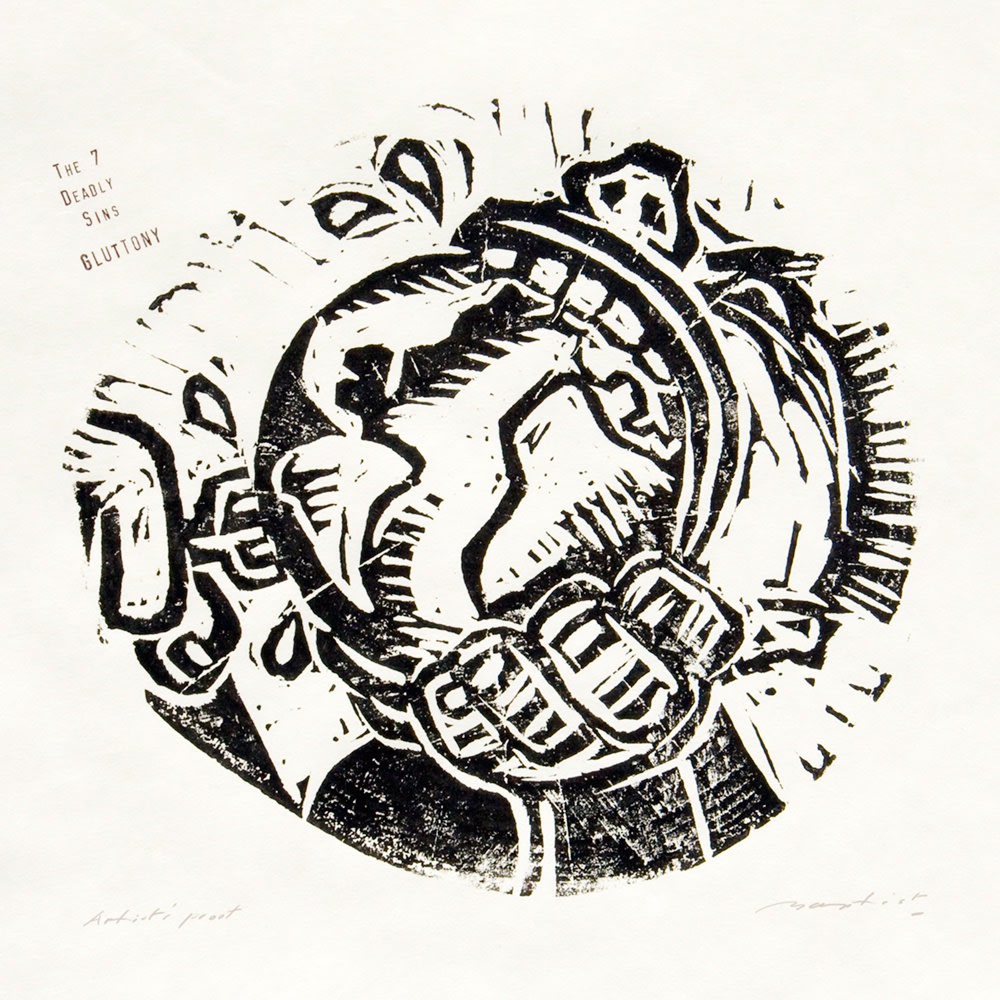

There were some ash tree logs drying and splitting in the garden, which gave me the idea that using wood that was changing, decomposing and actually destroying itself would be the ideal medium to use for woodcuts of The 7 Deadly Sins, which I had been working on in a sketchbook. As you can imagine, it was a struggle cutting into the end grain of the logs, using a mallet and carpenters’ chisels, but I finally managed to hack them out and after a lot of experiments managed to make a few editions of the woodcuts.

I tackled digital printmaking in a similar way by a mixture of trial and error. This was in the 1980s when information about Photoshop or a graphic pad was very hard to find. But it is amazing what you can do when you want to do something! The first work that I created were drawings I used to design some jewellery. The idea came from my time teaching drawing at a Yoga school in Crete. With an early Wacom graphic pad I drew very simple, block-like yoga figures on a computer, making patterns of them. The drawings were etched into silver and then I got help from friends in Germany to turn my designs into jewellery.

Digital work was not taken seriously in the 1990s - galleries dropped me, they just didn’t want to know. ‘The computer does it all for you’, was a frequent comment. It was years before it was accepted as an art form like an etching or a screenprint - there was a double-page article in the technical section of Printmaking Today in the Winter issue of 2007 in which I was questioned about computer-generated images by Anthony Dyson RE.

‘Gluttony’ Woodcut 26 x 26cm From the ‘7 Deadly Sins’’

Do you feel that you have ever landed on a particular ‘style’, or is it constantly changing and evolving?

I have never been able to be still… there’ll be plenty of time for that in the future! In the meantime, I’ll continue to follow Picasso’s thinking: ‘God is really only another artist. He invented the giraffe, the elephant and the cat. He has no real style. He just goes on trying other things.’

To explain little about ‘style’; I decided one spring to make some sketches of our garden which my wife Jean had designed. I couldn’t help noticing how quickly plants grow at that time of year. They were growing in much the same way as humans do, scrabbling around for space and territory, smothering rivals that get in their way. It is in the plants DNA, I learned from an article by Richard Dawkins, just as it is in ours. The almost violent movement of the growth over time began to dictate the way I painted the images. Another ‘style’ or just trying to explain natural phenomena, using paint and a brush? I just find that different ideas somehow lead me down different paths. It is just the way I work.

‘Summer day’ Acrylic 56 x 76cm

Part of Gerry's submission to become an RWS member

Despite your works often having rather serious undertones, one can’t help but smile looking at them. Is there something that you hope to achieve or convey through your art, or a reaction that you hope to provoke from the viewer?

Whatever I do, using humour or not, I have in mind that if Picasso’s amazingly brutal and moving painting ‘Guernica’ hasn’t changed the way the world thinks about war, what hope have I to provoke a reaction, let alone a reaction that makes a change? I really feel rather ineffective in that sense but I go on trying.

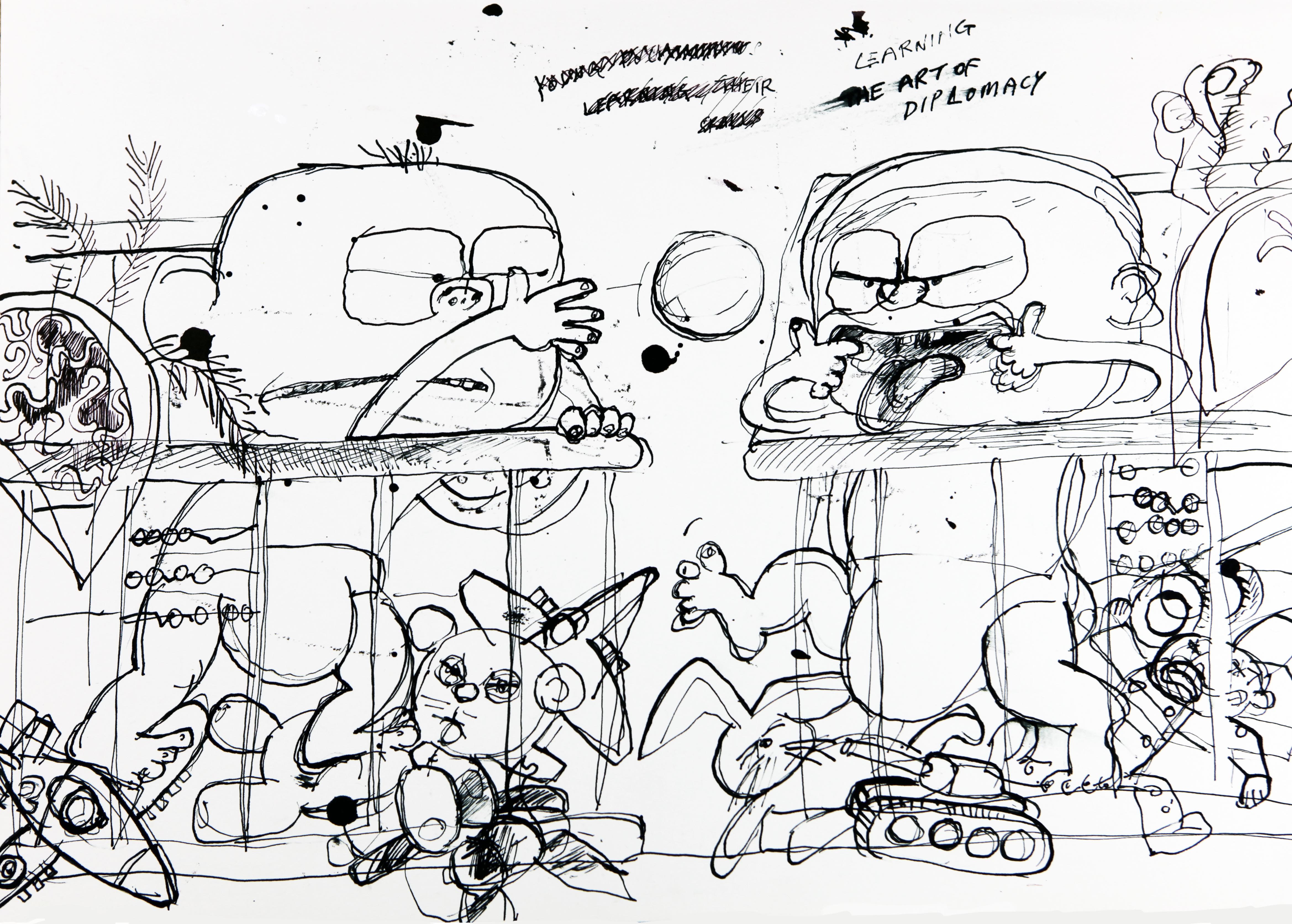

‘Learning the art of diplomacy’ Pen and ink sketch 29.7 x 42cm

What are some of the greatest joys – as well as the greatest challenges – of being an artist?

You just work because, as Jung puts it, ‘Art is an innate drive’. Of course you have doubts and wonder whether you really have anything worth saying but there seems to be no alternative but to carry on. The joy comes later when you look at an image and think that it has worked.

‘What is it that makes Burgers so appealing’ after Hamilton, Woodcut 30 x 40cm

What do you believe to be the role of an artist in society?

Art certainly adds another dimension to our world.

Look at a Damien Hirst’s cow, cut in half, it stops you and forces you think about mortality. It is a troubling piece of work. Or Graham Sutherland’s portrait of Winston Churchill which I saw it in the Tate many, many years ago. It was a magnificent portrait of a strong tough character, grown old. It is still alive in my memory. Or a small Paul Nash woodcut - I have only seen a print of it on a postcard, but it remains in my thoughts.

I can think of no better way to understand the importance of the role of an artist than watching a BBC2 series by historian, James Fox, called ‘Nature and Us: a History through Art’. (It will be on iPlayer.) It is an informative, thoughtful and wide-ranging view of art from the very beginning of human life – and the vital role art has played.

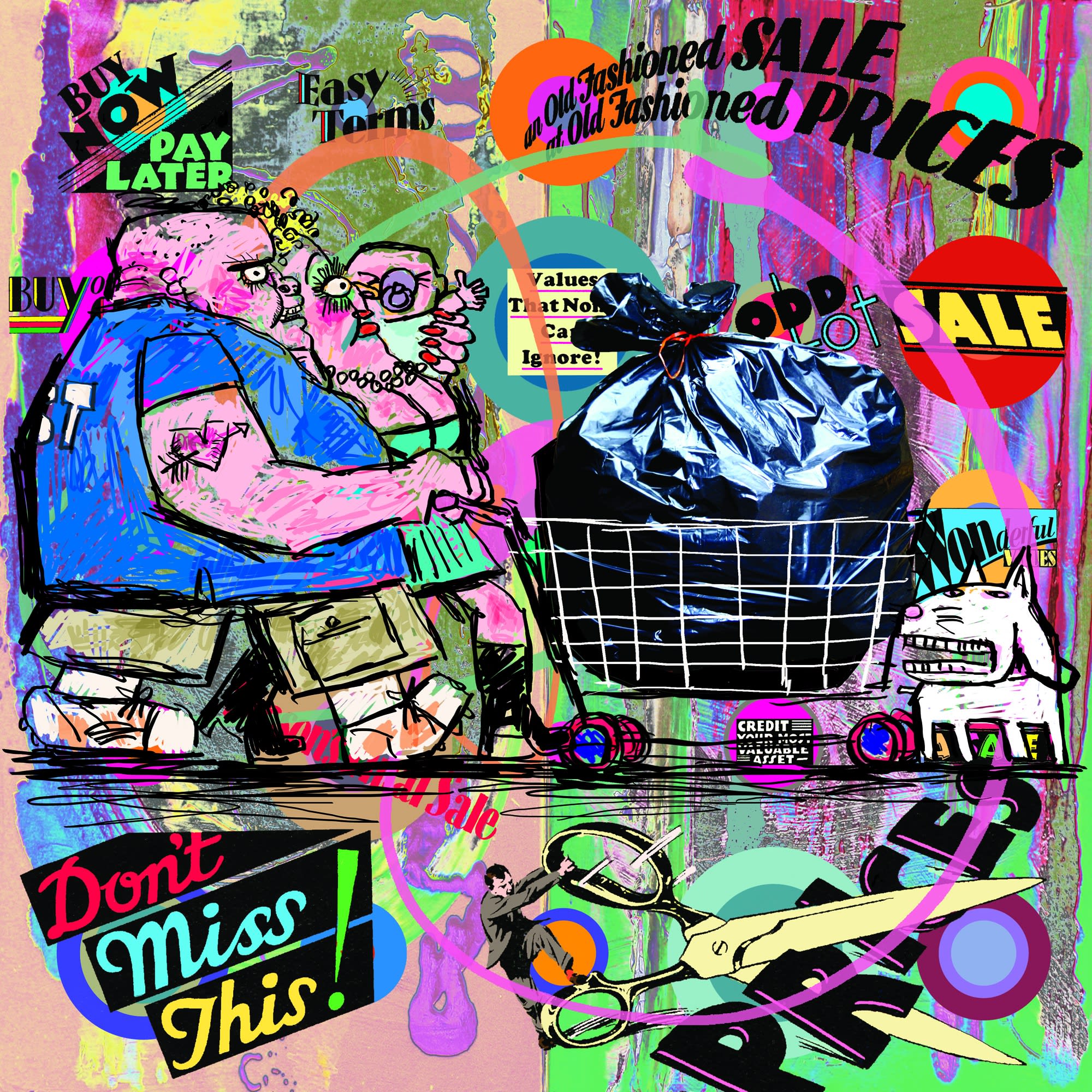

‘Supermarketman’, Digital Print 60 x 60cm

Part of Gerry's submission to become an RE member

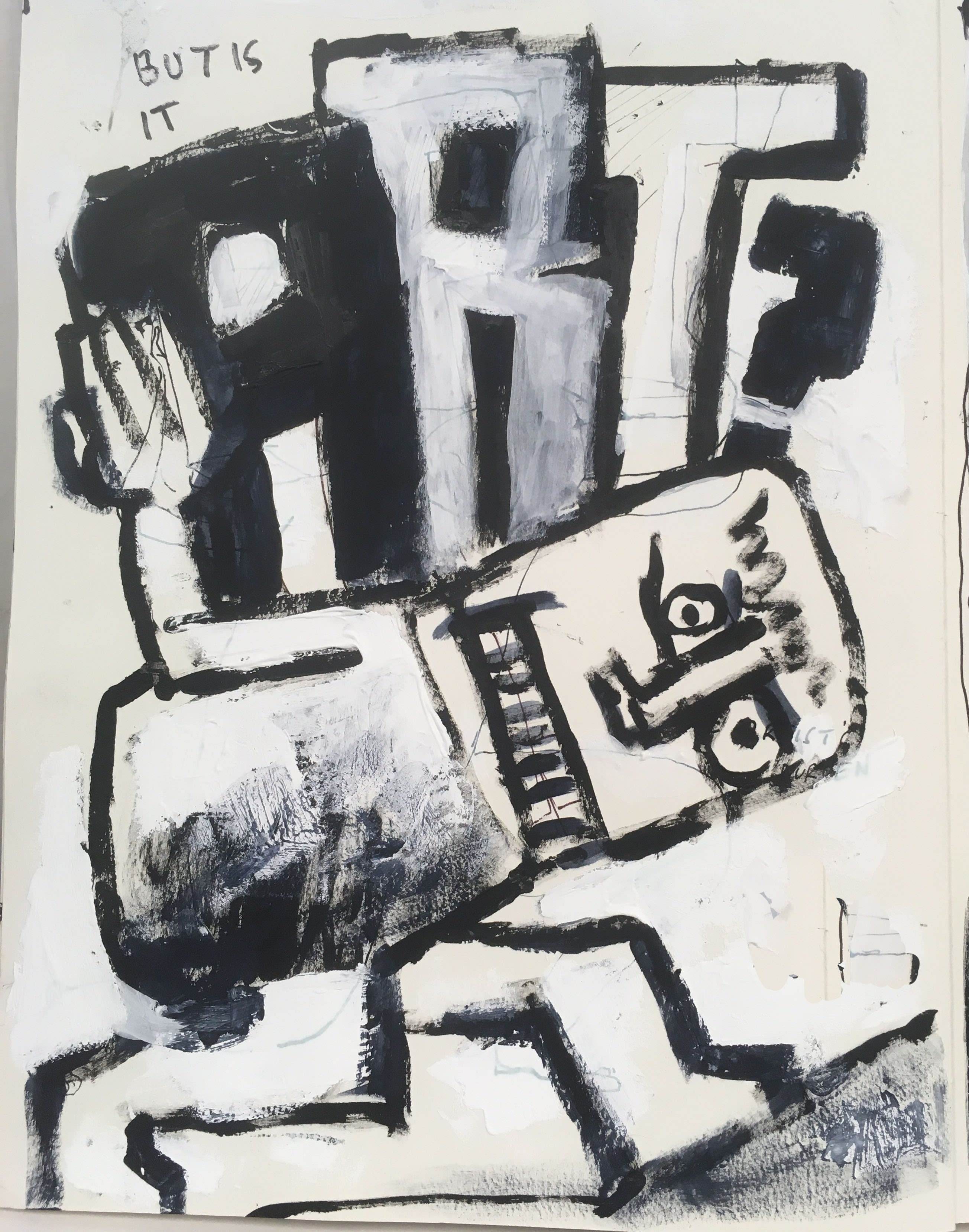

Do you think there is something that separates ‘good’ art from ‘bad’? Are there even such things as good or bad art?

If only we could put ‘art’ in a test tube and test whether it is good or bad.

To become a Member of the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS) or Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers (RE), artists apply by sending in examples of their work. Members of each Society spend a lot of time looking at the work, discussing and arguing about the merits of the submissions – and then vote for artists they believe are ‘good enough’ to be members. So, possibly that approach is the nearest thing we have to a test tube: it’s a ‘consensus of opinion’.

‘This is not what art is about’, Acrylic sketch 42 x 29.7cm

What’s next for you?

Earlier this year I was going through some of my work and found some abstract sketches which were drawn in the early 1960s, they were developed into large black abstract forms painted in oil on 8’ x 4’ board. At the time they seemed, in my mind, to be guardians or sentinels, dominating the landscape, protecting humans. But the ’60s were so exciting and full of life that I felt certain we didn’t need guardians – they were irrelevant, totally unnecessary – so I binned the paintings, keeping only a few marker-pen sketches.

Today, the thought of guardians resonated with me, enough for me to work on the abstracts again to see what I could do with them. The abstract forms begun to have a life of their own, turning into heads: guardians heads, spiritual beings; towering, powerful strong forms in the landscape attempting to protect us and the environment.

How can we get off the merry-go-round of life? Can we alter our DNA?

I feel I’m just fiddling while the world burns. And the Merry Go Round of life carries on...

Abstract from the 60s Marker pen

What advice would you give to aspiring and emerging artists?

Everyone has a talent of some of some sort.

If you spend your life worrying whether your art is any ‘good’ or what others think about it, your own fragile thoughts will be submerged or strangled even before they have seen the light of day.

Be curious about the world. Create work that is honest and unfettered by conventions. It is a struggle sometimes, but you will turn out to be you.

Let others decide whether the work is good or bad with their quality scales – you’ve put in all you can.

1. DON’T GIVE A DAMN about what others think.

2. ‘Trust yourself’ as Picasso said.

3. Believe in impossible things!

A footnote.

Back in 1991, I was in the queue to buy a ticket to get into The Fauve Landscape show at the RA when Francis Bacon joined the queue behind me. ‘Blimey Francis,’ I said, ‘don’t you get into RA shows for free?’ ‘No,’ he answered, ‘I have to queue like everyone else.’ We chatted about the Fauves and he suddenly said, ‘I wonder why they painted in those bright colours?’ before answering his own question with, ‘I suppose we shouldn’t ask.’ His comment made me realise that the Fauves didn’t give a damn about what others thought.

‘Guardian attempting to protect the Rain Forests’ Digital print with laser-cut Acrylic head 30 x 60cms

If you would like to find out more about Gerry, you can follow him on Instagram or visit his website here. You can also browse more of his artworks through the button below!

More like this on the Blog...

Read: A Brutalist Love-Affair: Interview with Paul Catherall RE

Read: The Poetry of the Everyday: Interview with Anita Klein PPRE Hon. RWS

Read: Interview with Akash Bhatt RWS

Read: Interview with Sumi Perera RE

Read: Interview with Peter Lloyd RE

Read / Watch: Relief Printing: In the Studio with Trevor Price RE