Between 23-28 November 2021, Bankside Gallery and Eton College are bringing together a selection of works from Eton’s artists in residence in the exciting Art Makes Art exhibition.

Three of Eton College's artists in residence taking part in this forthcoming exhibition are members of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers (RE) - Ade Adesina ARE, Anne Desmet RA RE and Katherine Jones RE. Given that we regularly exhibit RE members' work at Bankside Gallery, we were rather excited about this crossover! In the lead up to the exhibition we have run a short series of interviews with Ade, Anne and Katherine to find out a little more about their life and work, and hear all about their time spent as artists in residence at Eton College.

The next in our series is Anne Desmet RA RE, who specializes in wood engraving, linocut & collage. She is engaged with the evolution of the urban landscape and its testimony to the aspirations and experiences of humanity. She uses traditional printmaking techniques but draws on a variety of materials to create distinctive layered collages. Her work ranges from small scale, detailed examinations to sweeping panoramas viewed from a bird’s eye perspective.

Interview: Matilda Barratt in conversation with Anne Desmet RA RE.

Could you start by telling us a bit about yourself and your practice?

I am an artist-printmaker specializing in wood engraving and in mixed media printed collages, as well as linocuts, stone lithographs and monoprints. I was born and raised in Liverpool but have lived in London for 30+ years and had a very formative year living and working as a Rome Scholar in Printmaking at the British School at Rome in 1989-90 – a period which inspired the architectural direction of my work. For 15 years, I was Editor of “Printmaking Today” magazine (1998-2013) alongside working as an artist-printmaker. I’m also a writer – of 7 published books on printmaking and drawing to date, including the recent Ashmolean Museum catalogue: “Scene through Wood: A Century of Modern Wood Engraving” for an Ashmolean exhibition which I also curated. That show will be touring to the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester; and the Heath Robinson Museum, Middlesex, in 2022; and the St Barbe Museum in Lymington, Hampshire, in 2023.

Did you always know you wanted to be an artist? What are your earliest memories of creativity?

I was born with a serious abnormality of one of my hips and spent about 5 years of my childhood and adolescence (a few months here, a year there) in hospital having repeated – and largely unsuccessful – surgical procedures to try to correct it. In those days (mid 1960s to early ‘80s), orthopaedic surgery usually involved about eight weeks of enforced bedrest following each operation, before you were allowed up to start relearning how to walk. That meant, for me, seemingly endless months in hospital when I was not exactly “ill” but couldn’t get up and move about. I kept busy by reading and by drawing everything in sight – usually in pencil or black Biro – from cartoons of children in adjacent beds (which I certainly recall doing by age 9) to very detailed pencil studies of my hands and feet, a bowl of cherries on my bedside locker, the light bulb above my head, my face reflected in the bottom of a teacup and so on.

The features that these drawings all shared were that they were rarely bigger than A4 (as it’s hard to manage anything larger when you’re semi-reclined in bed) and they were very detailed because I had lots of time to pour into them. Drawing became something of an obsession so I did reach a point where I couldn’t imagine doing anything else, but the idea of trying to make art my profession came much later. I had no real awareness of art and artists, past or present, at that point and there was no culture of contemporary art that I was aware of in Liverpool in the 1960s/70s. So, in my late teens, when I decided to apply to study art rather than classics at university, I hadn’t really entertained the idea of being “an artist”. I think I still thought “art” would be a hobby I’d have to do in my spare time while working in some other field. Going to art school didn’t make me feel much more confident about how I might make art my living but it certainly loaded the dice against alternative career choices. When I applied to art school, I had a portfolio full of intensely detailed small drawings and had become particularly interested in chiaroscuro, fine detail and the interplay of black and white marks. Early on in my three years at the Ruskin School of Art (Oxford university), the then visiting tutor Joe Winkelman PPRE introduced me to woodcut while the excellent full-time printmaking tutor, Jean Lodge RE, introduced a wide range of other print techniques, all of which I tried. She thought wood engraving would suit me because it would enable me to lavish as much time and attention on relatively small works as I was already doing on one-off drawings, but I would be able to print an edition and sell each print for a much more affordable sum than would be viable for one-off pieces. However, more importantly, she felt that using engraving tools to cut end-grain boxwood would expand my mark-making repertoire and make my images more dynamic. She was right and I am unfailingly grateful to her.

Tell us a bit about your creative process…

There’s a particular graphic clarity about wood engraving that I find peculiarly satisfying. There’s a sense of resolution and decision-making about it. I find, for best results, that I have to plan a composition fairly carefully in advance so as not to make errors in the engraving. But there’s a fine balance between excessive planning and allowing the print to take on its own life to become something different from and more dynamic than its preparatory drawings/photos – of which there are always quite a few. If the print is successful, then it’s that sense of strength and dynamism in it that strongly appeals to me. I’ve never been drawn to painting – except for watercolour or ink wash drawings in my sketchbooks. Oil painting, in particular, never suited me because it doesn’t facilitate the graphic clarity of printmaking and it involves a very different mindset. With oil painting, there’s endless potential to change your mind and repeatedly change any part of a work at virtually any point. I like the fact that, with a wood engraving, once you start engraving the wood, you can’t erase anything you’ve done so there is a definite direction of travel from the very first marks you make!

You were the third wood engraver ever to be elected as a Royal Academician – quite the achievement!

Being elected a Royal Academician in 2011 was a huge surprise and still feels like a tremendous honour. There have actually been a fair few members in the RA’s history who have made wood engravings but only Charles Tunnicliffe (1901-79), Gertrude Hermes (1901-83) and I who have been elected specifically as engravers, on the strength specifically of our wood engravings. These are big shoes to fill – especially those of Hermes who I think may be the greatest engraver who has ever lived! Incidentally, like me, Tunnicliffe and Hermes were both RE members as well as RAs.

What is it that you love about the wood engraving medium?

It feels very satisfying to engrave into a beautiful piece of polished boxwood – and the natural shapes of some of the blocks – especially roundels – can suggest compositions in ways that rectangular etching plates or screenprinting frames might not. So, the wood itself can be inspiring. But also, in wood engraving there’s the wonderful creative joy of engraving light out of darkness – all the marks you make in the block being the parts that will be white paper in the print and all the uncut parts being those that will be rolled with ink and printed. It’s inexpressibly exciting to bring that light image out of darkness and to play with the wonderful potential for highly contrasted tones. My better drawings have always been those with highly contrasted areas of light and shade and wood engraving lends itself especially well to such effects, so I was immediately enthralled by it.

What first attracted you to printmaking?

I went to Oxford after a “gap year” in hospital having yet another leg operation. So, I didn’t do a Foundation Course prior to starting my Fine Art degree. Added to that, I had been educated at a rather poorly funded Liverpool comprehensive school so, although I was very adept at drawing, I had no painting or sculpture skills at all and had tried out only a fairly narrow range of art forms. However, having been led to understand that wide-ranging techniques would be taught as part of the degree course, it turned out that, in fact, most of the tutors assumed students had already undertaken oil painting etc (which those who’d been to private schools who, at the time, formed the vast majority of the Ruskin’s intake, all had) so these rather basic skills weren’t actually taught at all. It was, however, assumed that printmaking would be new to all students so many of its diverse techniques were taught thoroughly from an early stage. Until that point, in my first year as a student, I had only fairly vague notions about printmaking. If I thought of it at all, I associated it mostly with book illustrations. The fact that printmaking encompassed so many and varied ways of making original art came as quite a revelation. I was instantly hooked.

I understand that your printmaking scholarship to Rome in 1989 had a profound impact on you, sparking an interest in architecture, which would soon become a prominent theme in your work. Has the experience continued to influence your practice later down the line?

At school I was very interested in Latin – which I took for one of my A levels. I was especially interested in the Ancient Roman poet Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” with its fantastic stories of nymphs turning into trees or sea-monsters... I was also interested, at that time, in the fantastical/mathematical metamorphoses of Dutch artist M C Escher (1898-1972) – I had a poster of one of his woodcuts on my bedroom wall for most of my teenage years. I began to make drawings and later, at art school, prints that usually involved images of people – often friends or family – metamorphosing in some way or other that seemed to me to suggest something of their character and also, I hoped, embodied an idea of the passage of time. After I’d graduated from Oxford and, later, from London’s Central School of Art (where I did a postgraduate year), I was awarded a Rome Scholarship in Printmaking, which gave me a year to live and work as an artist in Rome (1989-90). I spent a lot of time there walking and sketching. Rome was a complete revelation to me. I’d never been there before. I was struck by the multi-layered nature of it – the fact that you can be walking down an ancient Roman road that sits on top of Etruscan tombs and you can walk into a church from Roman times that may have medieval remodeling and a Baroque dome and, above all that, you can see the TV aerials and satellite dishes of the 20th and 21st centuries. It felt like everywhere I looked I could see a span of over 2,000 years with all those centuries of change and metamorphosis all co-existing in our times. I found that really exhilarating. The dramatic light and shade of the sunlight on Rome’s buildings was also hugely inspirational. Its drama and theatricality really seemed to suit the wood engraving medium and my temperament. It didn’t take long before nearly all my prints were inspired by my sketchbook drawings of buildings and landscape in Rome and elsewhere – all places that seemed to encompass a sense of a vast span of time or timelessness within a single vista. So, in my mind, they are actually still about metamorphosis, in their way.

Is there something that you hope to achieve or communicate with your work?

My subject matter pulls in two directions: one body of work is essentially topographical but subject to metamorphoses; it relates to the slow passage of time and its cycles of construction and decay. I am also concerned with urban myths, intuitive architectural fantasies and histories of urban destruction and regeneration such as the biblical Tower of Babel, Italy’s Mt. Vesuvius and the Great Fire of London. I aim to suggest the timeless solidity, beauty, human aspiration, humour, hubris and folly that architectural forms can convey, as well as their impermanence and actual fragility and the effects of changing light and weather. A sense of lost civilisations of the past and the vulnerability and preciousness of our lives and urban cultures today – whether from war, terrorism, earthquake, volcano or weather events related to climate change – are ongoing underlying themes and underpin the thought processes behind most of my prints and printed collages. I hope my works may communicate some of these thoughts to the viewer and with increased urgency in these times of climate crisis. However, I’ve actually never wanted to be too prescriptive about the messaging in my works because often viewers see surprising and thought-provoking things in them that I hadn’t consciously considered or intended – and that’s fine too.

You will be exhibiting in Eton College’s forthcoming exhibition Art Inspires Art at Bankside Gallery. Could you tell us about your experience being an artist in residence at Eton College? And we’d love to hear more about the work that you will be showing in the exhibition…

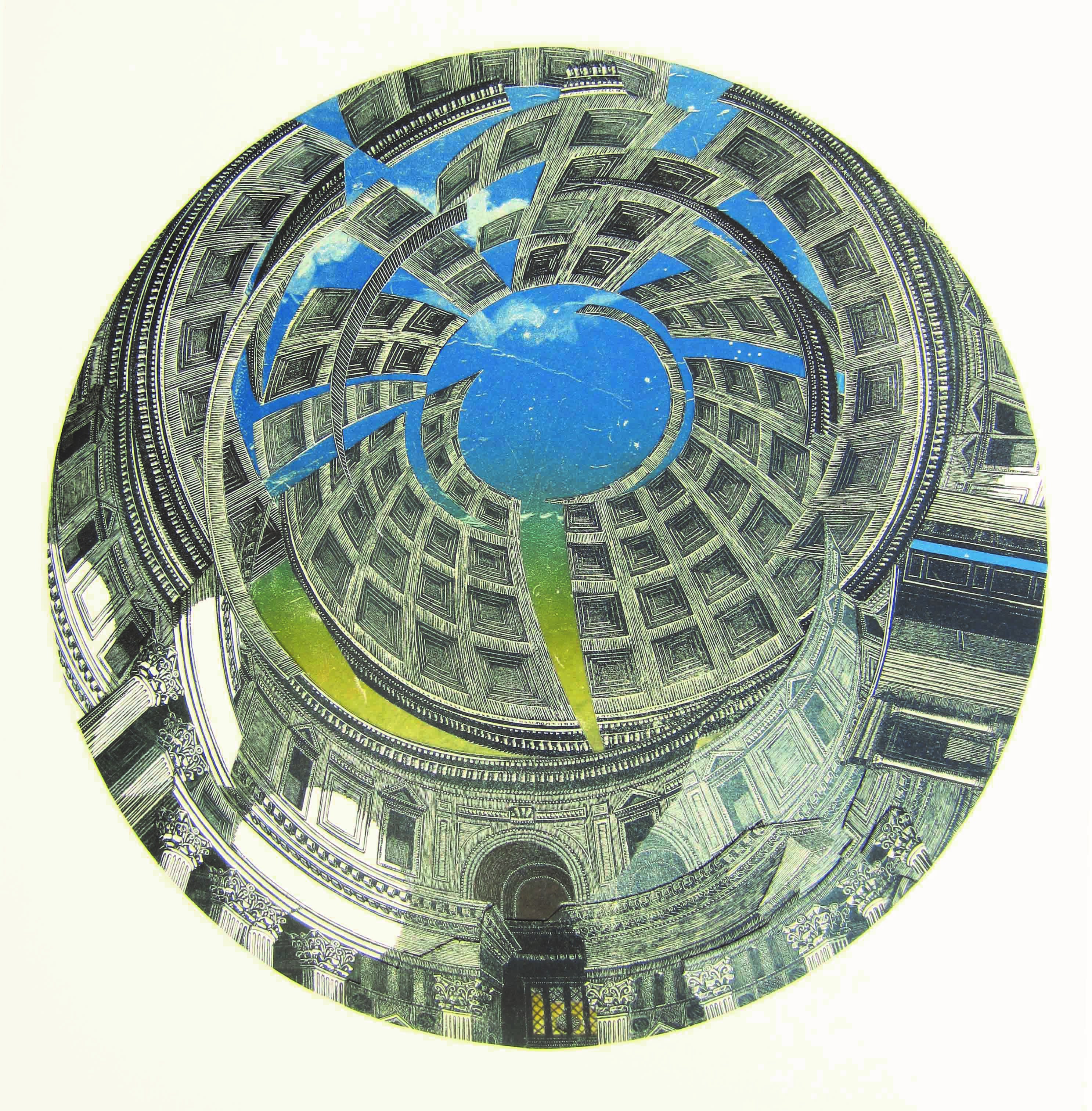

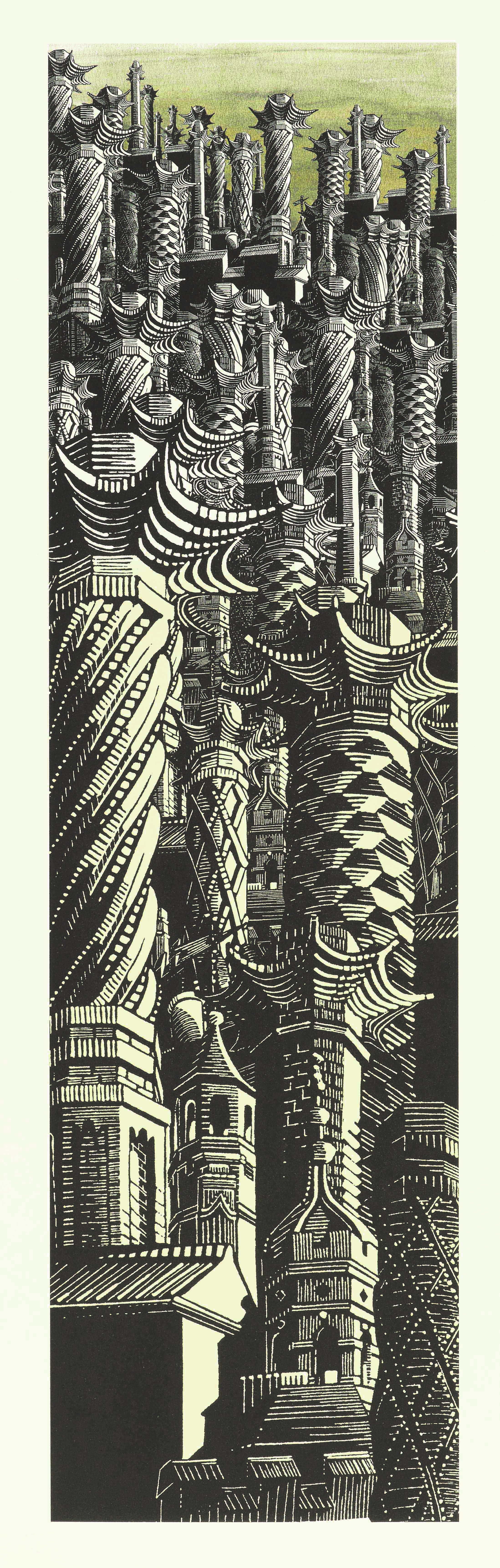

As artist-in-residence at Eton College (in spring 2016), I concentrated, primarily, on ‘looking up’, which later became the title of a multiple-block wood engraving which will be in the exhibition. Looking up, my attention was first caught by the distinctive red-brick Tudor chimneys on the college’s Foundation Building. Beginning by making pen and wash sketchbook studies and taking many photos, I later portrayed them in the engraving (also in the exhibition) entitled: “Towers and Tudor Chimneys”. It shows a substantial collection of Eton’s many and varied chimneys clustered together within an invented rooftop composition. Eton’s other architectural curiosities and idiosyncrasies also inspired my work during the residency. These included the chapel’s castellated turrets, out of which sprout tiny bell towers, and its elaborately contrived 1950s fan vault (ceiling) which, contrary to its construction in concrete, ambiguously suggests the lightness of airy, soaring materials. The College Library with its white neoclassical dome and mathematically configured stone-pineapple embellishments also inspired new engravings and these will all feature in the exhibition. In contrast to these (and other) images born of ‘looking up’, the view looking down from a window above the college’s print studio was the source for ‘Crossing the Courtyard’, an engraving of Eton boys traversing the space directly outside the Drawing Schools and Farrer Theatre. Working in collaboration with the college’s design department, two large lithographs were created in Photoshop, using repeated and manipulated details of my engravings to create two entirely invented compositions. One, entitled “Rotunda x 20”, is intended to suggest links between the architecture and ambition of Eton, London and ancient Rome, while the other: “Urban Jungle”, posits an ever-growing army of the college’s chimneys, which begin to evoke a dense, surreal, forest. These two prints were both printed, after my Eton residency had ended, at Hole Editions in Newcastle where I worked in collaboration with master-printer Lee Turner. “Urban Jungle” is a development of my wood engraving of Tudor-era chimneys. It used repeated elements of my “Towers and Tudor Chimneys” engraving rescaled, regrouped and multiplied many times to create a sense of a vast forest of man-made trees. I had in mind, when creating this image, Mervyn Peake’s wildly eccentric multi-turreted Castle Gormenghast from his “Gormenghast” fantasy series of Gothic novels (begun in 1946). I was also thinking about human-generated global warming and deforestation. There is intended irony and double meaning in the work’s title. The meaning of the phrase “urban jungle” is understood to describe an urban area filled with buildings and regarded as especially unwelcoming or dangerous, though the word “jungle” itself is dictionary-defined as an area of land overgrown with dense forest and tangled vegetation. I hope that the image in the context of its title suggests both a wild urban sprawl and also a sense of pollution associated with deforestation.

Is drawing an important part of your day-to-day life as well as your practice?

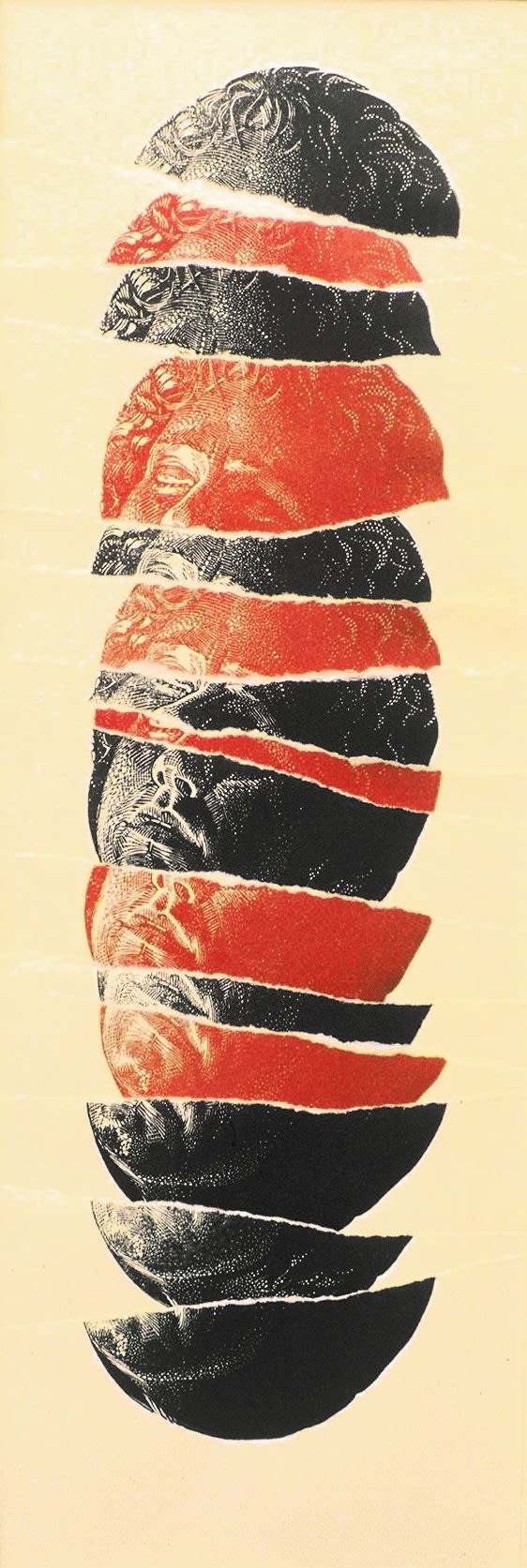

Wood engraving has actually become a more important urge in my life, over the years, than drawing – though the two are quite intertwined and I can’t actually do engraving without drawing. Wood engraving, for me, is actually an extended form of drawing. However, much as I love engraving, I’m not a speedy engraver and often feel a sense of frustration at how long each block takes me to engrave – which can be months sometimes. When I went to Rome, I had rather a sensory overload – there were suddenly so many potential ideas and images in my head that I’d need multiple lifetimes to engrave them all! I needed an additional creative outlet which would enable me to express some visual ideas more speedily. I had taken a small self-portrait engraving block, with which I wasn’t happy, to Rome. I’d printed it in a rust hue in London and, while finding my feet in Rome, had planned to reprint it in black to see if it worked better. I printed it but was still dissatisfied and so I tore up all the prints and went out drawing. When I came back to my room later, I was struck by the torn strips of black and red-brown engravings and found their random forms unexpectedly intriguing. I quickly shaped them into my first collage, a “Self-Portrait (Tower)”. It opened a door to the creation of all my subsequent collages. Although observational drawing remains a fundamental part of my practice, collage has become of equal importance and just as satisfying. The boundaries of my day-to-day life and my practice are blurred because I have a home-studio and am something of a workaholic. Drawing, engraving (which I consider another form of drawing) and collage-making all figure strongly.

For nearly a decade, all my collages were on paper or card but, when my two children were born 20-odd years ago and about 8-years of annual drawing trips (usually to Italy) were succeeded by UK family-holidays, usually at the beach, I couldn’t do much sketchbook-drawing as I’d be looking after and playing with the children instead. Initially I found it quite frustrating that having small children meant, to a large extent, that my drawing had to be put on hold, but then I started to notice items on the beach: razor-clam and oyster shells and interesting pebbles which seemed to suggest themselves as surfaces on which to collage. Some razor shells have orange and purple hues on their inner surfaces that look like expansive sunsets. I began picking them up and bringing them home to collage fragments of my prints onto them. Much like unusual-shaped engraving blocks, organic forms like seashells or pebbles often suggest their own compositional ideas. These collages in their turn suggested other possibilities so I have subsequently collaged on ceramic tiles and bits of pottery, shards of roofing slate, mirror fragments and the convex glass of clock faces. Each substrate is selected because it has some relationship with my subject matter. But it’s incredibly satisfying working with a combination of printmaking on paper and a range of unexpected found objects. I hope it brings something new and different to the wood engraving medium. I find cutting up, tearing and reassembling details of my prints into new collaged compositions a process not unlike drawing but reliant much more on intuition than direct observation. The two large lithographs aforementioned, which were created in Photoshop, are both, essentially, an extension of my collage methods except that the cutting and pasting in these images was all done digitally using scanned details of my engravings, rather than physically using paper, scissors and glue.

Over the past 18 months or so, it has been interesting to see so many people turn to creativity as a means of getting through. Have you found that your relationship to drawing and printing changed at all over this period?

Most of my seriously focused drawing for the last 30-odd years has taken place on trips to Italy, Greece or around the UK. In fact, the RA published two facsimile sketchbooks of many of my Italian and Greek sketches in 2016 and 2019 respectively (available to buy from all good bookshops!). Obviously, the pandemic made such sketching trips either impossible or, for me, too stressful to contemplate. So I have taken to looking at what I have around me in my home-studio rather than to looking so much for inspiration to the world outside. This has led me to begin a sequence of large new wood engravings that create illusions of assorted towers but these are towers made from household objects assembled into unusual still-life formations on a table in my studio. I have been photographing these in different light conditions and then developing the imagery into new wood engravings. I think it may mark a significant change of direction for my work.

Until the pandemic, I had continued to teach engraving in short courses and classes, from time to time, at various workshops, because I want the medium to continue and to grow in the future since it has far fewer practitioners to safeguard it, in the UK, than I would like. That teaching is just beginning to resume again now and it’s lovely to meet the participants, all of whom seem so happy to be able to learn new art skills face-to-face again rather than online.

Finally, what would be your advice to aspiring creatives who feel that a career in the art world seems out of reach?

Until the last eight years or so, in order to make a reasonable living, I had to combine my art career with other work, which included nine years (in the 1990s) as gallery administrator/publications manager at Bankside Gallery; art journalism; sporadic teaching at art schools; and, for 15 years, I was Editor of “Printmaking Today” magazine. I gave up that editorship in 2013, two years after I was elected to the RA, because I found I was now able to work full-time as an artist living on sales of my work. But I am someone who had no artist role-models or any contacts in the art world in my family and I also had a significant disability to contend with and I began my career at a time when women artists weren’t generally taken as seriously as their male counterparts. I was also not super-confident nor especially outgoing so sometimes it’s been rather an uphill struggle. However, I was always very hard-working and rather doggedly determined. I have had lots of exhibition rejections along the way – and still sometimes get those today – and earlier it took me two attempts to get onto a postgrad. art course, two attempts to get a Rome Scholarship and two attempts to be elected to the RE. So, I guess my main pieces of advice to any aspiring creatives would be that, if I could do it then you certainly can! But you need to be prepared to work really hard to make your work the best it can be; you may probably need to take on other jobs, at least for a while, to support your art; and don’t be deterred by failure: if you want something badly enough, be prepared to keep applying even in the face of repeated rejections. Also, I’d strongly recommend networking amongst other art students/teachers and artists and attending any exhibition private views that you can – again in the interests of networking. I have never done anything like enough networking really, but I now think a bit more of that could have opened some doors much more speedily for me! Also, be prepared to spend as much if not more time on the business/admin side of your career as on making the art itself. But if you don’t feel an urgent drive to be an artist rather than anything else, then you probably shouldn’t try! It has never really felt like a financially secure career and has often involved (in the early years) multi-tasking to make ends meet. But I couldn’t imagine a different life or one in which making art didn’t feature – I feel very blessed to have the freedom to do something I love – i.e. making art – every single day and even more so to be making a living doing it.

Read the next interview in our Art Makes Art series, with Ade Adesina RE. To find out more about the Art Makes Art exhibition, click here.

If you would like to find out more about Anne, you can follow her on Instagram or visit her website here. You can also browse more of her artworks through the button below!

More like this on the Blog...

Read: The Poetry of the Everyday: Interview with Anita Klein PPRE Hon. RWS

Read: Interview with Akash Bhatt RWS

Read: Interview with Sumi Perera RE

Read: Interview with Peter Lloyd RE

Read / Watch: Relief Printing: In the Studio with Trevor Price RE